Caring for the Caregivers: Research Informs Interventions to Ease Their Burden

“At least 17.7 million individuals in the United States are family caregivers of someone age 65 and older. As a society, we have always depended on family caregivers to provide the lion’s share of long-term services and supports for our elders. Yet the need to recognize and support caregivers is among the most significant overlooked challenges facing the aging U.S. population, their families, and society.”

— Families Caring for an Aging America, National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016

Dr. Catherine A. Riffin and Dr. Keiko Kurita

As life expectancies extend and increasing numbers of people are living with chronic illness and disabilities, more and more individuals are stepping into the role of caregiver. There is growing evidence today, however, of the physical, emotional, and financial toll caregiving can exact. Unrelenting stress and multiple competing priorities can impact the caregiver’s own health and well-being, and, in turn, jeopardize their ability to continue providing care. Clinicians and researchers in the Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center have brought the important issue of caregiver burden to the fore and are seeking ways to not only identify and assess caregivers’ needs, but also to provide interventions to support them.

Role of Primary Care

Catherine A. Riffin, PhD, a postdoctoral associate in medicine in the Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Care at Weill Cornell, is a developmental psychologist who just completed the T32 Training Program in Geriatric Clinical Epidemiology and Aging-Related Research at Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Riffin’s research focuses on family management of chronic illness, patient-caregiver communication, and the interpersonal processes that facilitate or undermine older adults’ chronic illness care. In 2017 her published research in these areas has appeared in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Aging and Mental Health, and Pain Medicine.

“My goal, and one of the reasons why I wanted to come to Weill Cornell, was to work very closely with the primary care physicians and other providers at NewYork-Presbyterian’s Irving Sherwood Wright Center on Aging,” says Dr. Riffin. The Wright Center provides both primary care and consultation to older adults in a multidisciplinary outpatient setting.

“Caregivers are essentially the ‘invisible’ patients,” says Dr. Riffin. “They’re often overburdened by their caregiving responsibilities. They accompany the patient to the doctor’s office and are highly involved in helping with the patient’s paperwork, coordinating care, managing medications, and myriad other things. It’s a time-consuming job. But a caregiver is usually viewed as someone to help with the patient’s care and not somebody with his or her own needs. Seeing a loved one go through a stroke or cancer can be very disturbing and can lead to a physical decline in the health and well-being of the caregiver.”

Dr. Riffin is working on developing a system that enables primary care providers to identify and assess family caregivers and their specific needs. “Through this system, we will be able to give caregivers a voice and link them to available resources and support in the community.”

Dr. Riffin’s qualitative research involves open-ended interviews with patients and caregivers about managing multimorbidities or multiple chronic health conditions. “We have found that there is wide variability in what patients want from their caregiver and what their caregiver is willing and able to help them with. For example, when a patient comes into the doctor’s office, he or she might not always want the caregiver to be there. In some instances, the patient may feel as though the caregiver interjects too much or speaks over him or her in conversations with the physician. The patient might want to speak confidentially with the doctor and describe in their own words what their health conditions are. Meanwhile, the caregiver may feel as though the patient is either incapable or unwilling to give the doctor the necessary details about his or her health conditions. These are just some of the dynamics that can play out in the physician’s office.”

“Caregivers are essentially the ‘invisible’ patients. They’re usually viewed as someone to help with the patient’s care and not somebody with his or her own needs.”

— Dr. Catherine A. Riffin

As Dr. Riffin explains, the physician also may not be aware of what is happening at home. Some patients may not want the caregiver to help with medication management. “Giving that information to providers is important because there are implications for treatment adherence and to ensure the patient is following recommended guidelines,” she says. “The caregiver can have a big impact on the patient’s willingness and ability to carry out their treatment.”

Providers also need to be aware of cultural differences in how families think about caregiving. “When I come in to speak with the caregiver and the patient, sometimes there are 10 people in the room. They are all caregivers or concerned family members and they all want to give some input. Even if one person is the designated caregiver to accompany the patient to the physician’s visit, the provider should be aware that there may be other people at home who have very strong views about the patient’s care and who may bear an impact on the patient’s health behaviors and ability to manage his or her health conditions.”

Impact of Cognitive Decline

Keiko Kurita, PhD, MPH, is a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell and in her second year of training in the National Institutes on Aging Postdoctoral Training Program in Behavioral Geriatrics (T32). Dr. Kurita’s research centers on understanding how declines in cognitive function and the treatment of chronic illnesses interact with one another and using this knowledge to improve the psychological well-being of older adults.

“Literature suggests that family caregivers of patients with very serious, stressful diseases, such as Parkinson’s, dementia, or stroke, can have physical and cognitive challenges compared to age-matched individuals who are not caregivers.”

— Dr. Keiko Kurita

“Many caregivers of older adult patients are older adults themselves,” says Dr. Kurita. “They may be spouses or adult children. For example, an adult child of a 90-year-old person can be 65 or 70 years old. So caregivers can also have illnesses and declines in cognitive function.”

Dr. Kurita is studying the extent to which mild cognitive impairment in patients and their family caregivers can affect the patient’s hospitalization outcomes, medical decisions, and advance care planning. “Literature suggests that family caregivers of patients with very serious, stressful diseases, such as Parkinson’s, dementia, or stroke, can have physical and cognitive challenges compared to age-matched individuals who are not caregivers,” says Dr. Kurita. “If this is true, care and decision-making during hospitalization could be compromised if caregivers are having difficulty with memory, attending to information, or comprehension. However, this potential issue hasn’t been well-studied.”

Dr. Kurita launched a pilot study to gauge the prevalence of these issues and interviewed patients and their caregivers at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment, to determine their associations with illness understanding, medical preferences, advance care planning, discharge expectations, and hospitalization outcomes. The patients’ physicians and healthcare providers were also interviewed following the patients’ discharge to assess the degree to which the patients and caregivers understanding and expectations were consistent with the providers’ views.

“The MoCA scale ranges from zero to 30. We found that a notable proportion of both patients and caregivers scored below the cutoff of what’s considered normal,” says Dr. Kurita. “We are finding evidence that mild cognitive impairment exists in hospitalized patients and caregivers, so I do believe that we should continue with the study to see if it impacts advance care planning and hospitalization outcomes.”

One study that led to Dr. Kurita’s present research was just published in the January 3, 2018 online issue of the Journal of Palliative Medicine. Dr. Kurita has applied for the National Institutes of Health Career Development (K) Award to continue her research at Weill Cornell.

Caregiving in the Home Hospice Setting

Dr. Veerawat Phongtankuel

Veerawat Phongtankuel, MD, a geriatrician at Weill Cornell, is particularly interested in assisting caregivers who provide home hospice care. “Caregivers certainly impact the patient’s quality of care at the end of life. These are typically informal caregivers who are usually children, spouses, or other relatives,” says Dr. Phongtankuel. “With home hospice care, a visiting team of providers comes on an as needed basis. Through our research, we’ve found that nurses visit patients, on average, about twice a week. During the other parts of the day and week, patients are typically being cared for by their informal caregivers.”

Dr. Phongtankuel’s research centers on home hospice care and its impact on caregiving. “In our current study, we are contacting caregivers via phone two to three weeks after their loved one has been discharged from home hospice,” he says. The phone interview consists of questions to examine the caregiver’s perception of their loved one’s symptoms, for example, their pain, shortness of breath, lethargy, and nausea and vomiting.

“We also ask them about the burden they experienced while caring for their loved one on hospice,” continues Dr. Phongtankuel. “We’re looking at data now and finding that there is a significant portion of caregivers who are overburdened as they try to manage medications and direct the daily care needs of the patient.”

Dr. Phongtankuel recognizes that sometimes the caregivers’ needs are not recognized or met because of their secondary role on the care team. “But they are so important in terms of managing and taking care of the patient,” he says. “We’re trying to identify those caregivers who are at high risk for burden and whether external factors or internal factors are contributing to that. Some potential risk factors include caregivers with high levels of anxiety and/or depression. We are hoping to be able to target those caregivers with interventions so that they feel supported during this intense period of caregiving.”

“We are looking into tools that can help better communicate and detect caregiver burden earlier so that the hospice team can proactively intervene before a poor outcome occurs.”

— Dr. Veerawat Phongtankuel

“There are symptoms experienced by the patient that can be very distressing to the caregiver, especially when the patient is dying,” adds Dr. Phongtankuel. “Having more nursing support for someone nearing the end of their life can help. Visits from a spiritual counselor or a social worker can also play a significant role in relieving some of the burden and distress experienced by the caregiver and/or the patient.”

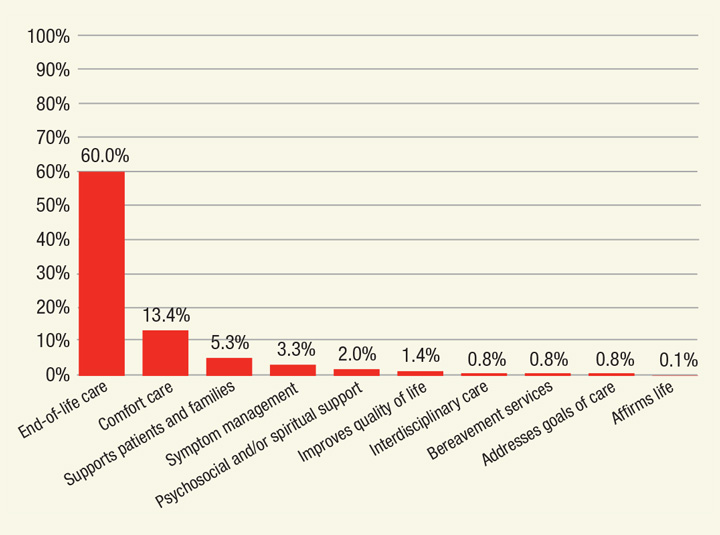

Participants Awareness of Hospice

n=664 responders

The American Journal of Hospital and Palliative Care. (2018 Mar)

Click for a larger view.

In fact, a recent study by Dr. Phongtankuel and his colleagues at Weill Cornell found that “despite the documented benefits of palliative and hospice care on improving patients’ quality of life, these services remain underutilized. Multiple factors limit the utilization of these services, including patients’ and caregivers’ lack of knowledge and misperceptions.”

The Weill Cornell team is also considering technology as a possible intervention. “One of the challenges of home hospice care is that nurses are unable to visit patients on a daily basis,” says Dr. Phongtankuel. “Telemedicine may help complement existing hospice care and support caregivers at increased risk for caregiver burden through better communication. We are looking into tools that can help better communicate and detect caregiver burden earlier so that the hospice team can proactively intervene before a poor outcome occurs. We believe our research will give us important insights into caregiving at the end of life. Our goal is to develop interventions and resources to assist and support caregivers in their role.”

Reference Articles

Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Kozlov E, Shen MJ, Adelman RD, Reid MC. Awareness and misperceptions of hospice and palliative care: A population- based survey study. The American Journal of Hospital and Palliative Care. 2018 Mar;35(3):431-39.

Phongtankuel V, Adelman RD, Trevino K, Abramson E, Johnson P, Oromendia C, Henderson CR Jr., Reid MC. Association between nursing visits and hospital-related disenrollment in the home hospice population. The American Journal of Hospital and Palliative Care. 2018 Feb;35(2):316-23.

Kurita K, Reid MC, Siegler EL, Diamond EL, Prigerson HG. Associations between mild cognitive dysfunction and end-of-life outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2018 Jan 3. [Epub ahead of print]

Phongtankuel V, Paustian S, Reid MC, Finley A, Martin A, Delfs J, Baughn R, Adelman RD. Events leading to hospital-related disenrollment of home hospice patients: A study of primary caregivers’ perspectives. The American Journal of Hospital and Palliative Care. 2017 Mar;20(3):260-65.

Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Lampa K, Reid MC, Eiss BM, Bhatia S, Adelman RD. Examining the role of primary care physicians and challenges faced when their patients transition to home hospice care. The American Journal of Hospital and Palliative Care. 2017 Jan 1. [Epub ahead of print]