A New Pancreatitis Program: Comprehensive Care for Progressive Pancreatic Disease

Dr. John M. Poneros

The management of acute and chronic pancreatitis requires the skills and expertise of medical and surgical gastroenterology specialists who can offer patients a wide range of treatment modalities. “Pancreatitis can be a difficult disease entity to treat,” says John M. Poneros, MD, Medical Director of the newly established Pancreatitis Program at NewYork-Presbyterian/ Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “These patients can experience episodes of chronic pain or intermittent severe attacks of pancreatitis requiring hospitalization. They can also be understandably anxious about getting their next attack or whether or not they’re at risk for cancer. Given our experience and the enormous volume of patients with pancreatic disease that we see here at Columbia, we felt that it was valuable to formalize our treatment of these patients with a full-service program.”

“Given our experience and the enormous volume of patients with pancreatic disease, we felt that it was valuable to formalize our treatment of these patients with a full-service program.”

— Dr. John M. Poneros

Dr. Beth A. Schrope

With funding from the Diller-von Furstenburg Family Foundation, the Pancreatitis Program, part of Columbia’s Pancreas Center, launched in 2018 under the leadership of Dr. Poneros and Beth A. Schrope, MD, PhD, Surgical Director. As a major referral center for other hospitals, the Columbia team frequently accepts patients with complex disease requiring tertiary care. “We’re able to offer multidisciplinary care for these patients that is not as easily available at other institutions, for example, a patient with necrotizing pancreatitis who requires invasive treatment, or a patient with a fever who is not responding to antibiotics and has a significant amount of inflammation in their abdomen,” says Dr. Poneros. “We’re able to accept these patients for transfer and help provide a better outcome.”

The program offers minimally invasive treatment approaches that include endoscopic cystogastrostomy and endoscopic necrosectomy for patients that previously would have undergone open surgery in order to remove infected necrotic tissue.

In addition to the latest medical, endoscopic, and surgical treatments, and nutritional support, genetic testing is available for patients with idiopathic recurrent acute pancreatitis. “With genetic testing and cutting-edge endoscopic imaging capabilities, we’re able to go that extra mile in figuring out whether there’s an intervenable etiology to their pancreatitis,” explains Dr. Poneros. “Often there will be an unrecognized mutation that might be contributing to the patient’s symptoms. We also convene a weekly multidisciplinary conference to review all of our complicated pancreatic cases, which is attended by surgeons, radiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and other pancreatologists.”

When Surgery is Necessary: Total Pancreatectomy and Auto Islet Transplantation

“My philosophy is that surgery for chronic pancreatitis is the last stop,” says Dr. Schrope, who is among some 20 surgeons in the country — and who was the first in Manhattan — to perform total pancreatectomy with autologous islet cell transplantation. “I recommend surgery only after other nonsurgical therapies have been exhausted. Nutritional management and endoscopic therapies can be very useful in patients with this disease. I want all of these things to have been tried prior to considering surgery, and then my approach is as long as we can relieve the patient’s pain, let’s keep as much of the pancreas as possible.”

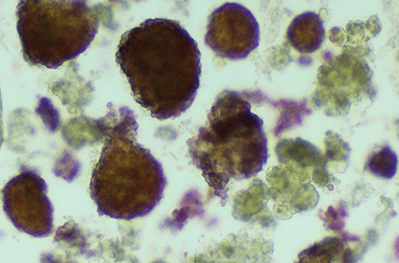

Total removal of the pancreas results in the likely development of diabetes. During the pancreatectomy, the surgical team removes the pancreas, isolates the insulin-secreting islet cells, and then injects the islet cells into the patient’s liver, where, hopefully, they take root and continue to produce insulin. “Removing the whole pancreas significantly improves or even eliminates the pain in over 90 percent of patients who undergo the procedure,” says Dr. Schrope. “And, while islet cell transplantation may enable the patient to continue producing isulin, the procedure is not always successful. A third of patients will make some insulin, but they will still need to take insulin. Another third will be insulin free for some time — four years, seven years, 10 years — but eventually the islets will fail and then the patients will become diabetic. But one-third of the time the procedure won’t work at all — the pancreas has been too damaged, the islet cells don’t engraft, and the patients don’t make any insulin appreciably.”

Dr. Schrope tries to perform a surgery that is short of a total pancreatectomy, if possible. “Can I take only part of the pancreas,” she asks, “or can I just reroute the pancreas depending on what the anatomy looks like so that we can save the pancreas to keep those islets working.”

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of sample from islet chamber. Free islets are dark red; acinar tissue debris is lighter yellow.

Dr. Poneros and Dr. Schrope collaborate on the treatment plan of each patient, taking into account the etiology of the pancreatitis when recommending specific therapies. “If it’s due to alcohol and you know that the patient has stopped drinking, hopefully they won’t get any more pancreatitis and there’s no need to operate,” says Dr. Schrope. “Sometimes it’s a sequella of one very bad attack of acute pancreatitis from gall stones that results in scarring of the pancreas. There is also autoimmune pancreatitis, a rare entity thought to be caused by the body’s immune system attacking the pancreas. Hyperlipidemia is another cause.”

Of all the patients for which Dr. Schrope has performed total pancreatectomy and auto islet transplantation, hereditary pancreatitis is a factor in about 30 percent. “In certain types of genetic pancreatitis there is a significantly increased risk of getting pancreatic cancer, so we work that into our treatment plan,” she says. “If the patient has the PRSS1 gene defect, for example, there is about a 10-fold increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Even before islet cell therapy became popular, we would remove the pancreas in these cases to avoid pancreatic cancer in the future. And now with islets, as long as we’re fairly reassured that the patient has a benign disease, we can take out the pancreas and give the patient their islet cells at least to try to avoid the diabetes.”

“We’re realizing that we need to be aggressive with progressive pancreatic disease, rather than accepting the notion that there’s not much to offer these patients in terms of stopping the march to chronic pancreatitis and potentially pancreatic cancer,” adds Dr. Poneros. “Our goal is to intervene to help stem that tide, whether it’s endoscopically, medically, surgically, or one day, genetically. We want referring physicians to know that we have the resources and the expertise to help them manage these very challenging patients.”

Reference Articles

Guo A, Poneros JM. The role of endotherapy in recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 2018 Oct;28(4):455-76.

Schrope B. Total pancreatectomy with autologous islet cell transplantation. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 2018 Oct;28(4):605-18.

Related Publications

Redefining Selection Policies for HCC Liver Transplantation