Health Library

Vaginal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

- General Information About Vaginal Cancer

- Stage Information for Vaginal Cancer

- Treatment Option Overview for Vaginal Cancer

- Treatment of Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (VaIN)

- Treatment of Stage I Vaginal Cancer

- Treatment of Stages II, III, and IVa Vaginal Cancer

- Treatment of Stage IVb Vaginal Cancer

- Treatment of Recurrent Vaginal Cancer

- Latest Updates to This Summary (02 / 16 / 2024)

- About This PDQ Summary

General Information About Vaginal Cancer

Carcinomas of the vagina are uncommon tumors comprising about 2% of the cancers that arise in the female genital system.[1] Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for approximately 80% to 90% of vaginal cancer cases and adenocarcinoma accounts for 5% to 10% of vaginal cancer cases.[1]

Rarely, melanomas (often nonpigmented), sarcomas, small-cell carcinomas, lymphomas, or carcinoid tumors have been described as primary vaginal cancers. The natural history, prognosis, and treatment of other primary vaginal cancers are different and are not covered in this summary.

Distant hematogenous metastases occur most commonly in the lungs, and, less frequently, in the liver, bone, or other sites.[1]

The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system classifies tumors in the vagina that involve the cervix of women with an intact uterus as cervical cancers.[2] Therefore, tumors that originated in the apical vagina but extend to the cervix are classified as cervical cancers. For more information, see Cervical Cancer Treatment.

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from vaginal and other female genital cancer in the United States in 2024:[3]

- New cases: 8,650.

- Deaths: 1,870.

Anatomy

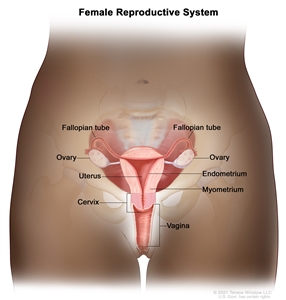

Normal female reproductive system anatomy.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for vaginal cancer include the following:

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. SCC of the vagina is associated with a high rate of infection with oncogenic strains of HPV. SCC of the vagina and SCC of the cervix have many common risk factors.[4,5,6] HPV infection has also been described in a case of vaginal adenocarcinoma.[6] For more information, see Cervical Cancer Treatment.

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero. A rare form of adenocarcinoma, known as clear cell carcinoma, occurs in association with in utero exposure to DES, with a peak incidence before age 30 years. This association was first reported in 1971.[7] The incidence of this disease, which is highest for those exposed during the first trimester, peaked in the mid-1970s, reflecting the use of DES in the 1950s. It is extremely rare now.[1] However, women with a known history of in utero DES exposure should be carefully monitored for possible presence of this tumor. (This association was mainly applicable to vaginal cancers diagnosed in younger women since adenocarcinomas that are not associated with DES exposure occur primarily during postmenopausal years.)

Vaginal adenosis is most commonly found in young women who had in utero exposure to DES and may coexist with a clear cell adenocarcinoma, although it rarely progresses to adenocarcinoma. Adenosis is replaced by squamous metaplasia, which occurs naturally, and requires follow-up but not removal.

- History of hysterectomy. Women who have had a hysterectomy for benign, premalignant, or malignant disease are at risk of vaginal carcinomas.[8] In a retrospective series of 100 women studied over 30 years, 50% had undergone hysterectomy before the diagnosis of vaginal cancer.[8] In the posthysterectomy group, 31 of 50 women (62%) developed cancers limited to the upper third of the vagina. In women who had not previously undergone hysterectomy, upper vaginal lesions were found in 17 of 50 women (34%).

Clinical Features

Although early vaginal cancer may not cause noticeable signs or symptoms, possible signs and symptoms of vaginal cancer include the following:

- Metrorrhagia.

- Dyspareunia.

- Pelvic pain.

- Vaginal mass.

- Dysuria.

- Constipation.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The following procedures may be used to diagnose vaginal cancer:

- History and physical examination.

- Pelvic examination.

- Cervical cytology (Pap smear).

- HPV testing.

- Colposcopy.

- Biopsy. If the cervix is intact, biopsies are mandatory to rule out a primary carcinoma of the cervix. Carcinoma of the vulva should also be ruled out.

Prognostic Factors

Prognosis depends primarily on the stage of disease, but survival is reduced among women with the following features:

- Age older than 60 years.

- Symptomatic at the time of diagnosis.

- Lesions of the middle and lower third of the vagina.

- Poorly differentiated tumors.

In addition, the length of vaginal wall involvement has been found to be associated with survival and stage of disease in patients with vaginal SCC.

Follow-Up After Treatment

Similar to other gynecologic malignancies, the evidence base for surveillance after initial management of vaginal cancer is weak because of a lack of randomized or prospective clinical studies.[9] There is no reliable evidence that routine cytological or imaging procedures in patients improves health outcomes beyond what is achieved by careful physical examination and assessment of new symptoms. Therefore, outside the investigational setting, imaging procedures may be reserved for patients in whom physical examination or symptoms raise clinical suspicion of a recurrence or progression.

References:

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

- Vagina. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 641–7.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2024. American Cancer Society, 2024. Available online. Last accessed June 21, 2024.

- Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM, et al.: A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecol Oncol 84 (2): 263-70, 2002.

- Parkin DM: The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 118 (12): 3030-44, 2006.

- Ikenberg H, Runge M, Göppinger A, et al.: Human papillomavirus DNA in invasive carcinoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol 76 (3 Pt 1): 432-8, 1990.

- Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Poskanzer DC: Adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. N Engl J Med 284 (15): 878-81, 1971.

- Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J: A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecol Oncol 56 (1): 45-52, 1995.

- Salani R, Backes FJ, Fung MF, et al.: Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204 (6): 466-78, 2011.