Health Library

Rectal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

- General Information About Rectal Cancer

- Cellular Classification and Pathology of Rectal Cancer

- Stage Information for Rectal Cancer

- Treatment Option Overview for Rectal Cancer

- Treatment of Stage 0 Rectal Cancer

- Treatment of Stage I Rectal Cancer

- Treatment of Stages II and III Rectal Cancer

- Treatment of Stage IV and Recurrent Rectal Cancer

- Latest Updates to This Summary (02 / 12 / 2025)

- About This PDQ Summary

General Information About Rectal Cancer

Incidence and Mortality

It is difficult to separate epidemiological considerations of rectal cancer from those of colon cancer because studies often consider colon and rectal cancer together (i.e., colorectal cancer).

Worldwide, colorectal cancer is the third most common form of cancer. In 2022, there were an estimated 1.93 million new cases of colorectal cancer and 903,859 deaths.[1]

Estimated new cases and deaths from rectal and colon cancer in the United States in 2025:[2]

- New cases of rectal cancer: 46,950.

- New cases of colon cancer: 107,320.

- Deaths: 52,900 (rectal and colon cancers combined).

Colorectal cancer affects men and women almost equally. Among all racial groups in the United States, Black individuals have the highest sporadic colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates.[3,4]

Anatomy

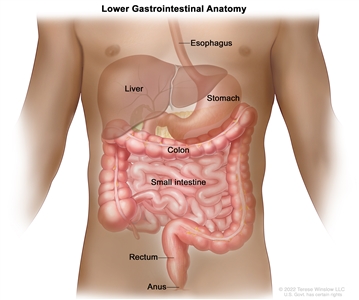

Anatomy of the lower gastrointestinal (digestive) system.

The rectum is located within the pelvis, extending from the transitional mucosa of the anal dentate line to the sigmoid colon at the peritoneal reflection. By rigid sigmoidoscopy, the rectum measures between 10 cm and 15 cm from the anal verge.[5] The location of a rectal tumor is usually indicated by the distance between the anal verge, dentate line, or anorectal ring and the lower edge of the tumor, with measurements differing depending on the use of a rigid or flexible endoscope or digital examination.[6]

The distance of the tumor from the anal sphincter musculature has implications for the ability to perform sphincter-sparing surgery. The bony constraints of the pelvis limit surgical access to the rectum, which results in a lower likelihood of attaining widely negative margins and a higher risk of local recurrence.[5]

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for colorectal cancer include the following:

- Family history of colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative.[7]

- Personal history of colorectal adenomas, colorectal cancer, or ovarian cancer.[8,9,10]

- Hereditary conditions, including familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer [HNPCC]).[11]

- Personal history of long-standing chronic ulcerative colitis or Crohn colitis.[12]

- Excessive alcohol use.[13]

- Cigarette smoking.[14]

- Race and ethnicity: African American.[15,16]

- Obesity.[17]

Screening

Evidence supports screening for rectal cancer as a part of routine care for all adults aged 50 years and older, especially for those with first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer. Reasons include the following:

- Incidence of the disease in adults 50 years and older.

- Ability to identify high-risk groups.

- Slow growth of primary lesions.

- Better survival of patients with early-stage lesions.

- Relative simplicity and accuracy of screening tests.

For more information, see Colorectal Cancer Screening.

Clinical Features

Similar to colon cancer, symptoms of rectal cancer may include:[18]

- Rectal bleeding.

- Change in bowel habits.

- Abdominal pain.

- Intestinal obstruction.

- Change in appetite.

- Weight loss.

- Weakness.

With the exception of obstructive symptoms, these symptoms do not necessarily correlate with the stage of disease or signify a particular diagnosis.[19]

Diagnostic Evaluation

The initial clinical evaluation may include:

- Physical exam and history.

- Digital rectal exam.

- Colonoscopy.

- Biopsy.

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay.

- Immunohistochemistry.

- DNA mismatch repair/microsatellite instability (MSI) testing.

Physical examination may reveal a palpable mass and bright blood in the rectum. Adenopathy, hepatomegaly, or pulmonary signs may be present with metastatic disease.[6] Laboratory examination may reveal iron-deficiency anemia and electrolyte and liver function abnormalities.

Prognostic Factors

The prognosis of patients with rectal cancer is related to several factors, including:[6,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]

- Tumor adherence to or invasion of adjacent organs.[20]

- Presence or absence of tumor involvement in the lymph nodes and the number of positive lymph nodes.[6,21,22,23,24]

- Presence or absence of distant metastases.[6,20]

- Perforation or obstruction of the bowel.[6,28]

- Presence or absence of high-risk pathological features, including:[26,27,29]

- Positive surgical margins.

- Lymphovascular invasion.

- Perineural invasion.

- Poorly differentiated histology.

- Circumferential resection margin (CRM) or depth of penetration of the tumor through the bowel wall.[6,25,30] Measured in millimeters, CRM is defined as the retroperitoneal or peritoneal adventitial soft-tissue margin closest to the deepest penetration of the tumor.

- Presence of MSI that results from impaired DNA mismatch repair.

Only disease stage (designated by tumor [T], nodal status [N], and distant metastasis [M]) has been validated as a prognostic factor in multi-institutional prospective studies.[20,21,22,23,24,25] A major pooled analysis evaluating the impact of T and N stage and treatment on survival and relapse in patients with rectal cancer who are treated with adjuvant therapy confirmed these findings.[31]

Mismatch repair deficiency occurs in 5% to 10% of patients with rectal adenocarcinomas. Mismatch repair–deficient tumors do not respond well to chemotherapy applied in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic settings.[32,33,34] In a population-based series of 607 patients aged 50 years or younger at the time of diagnosis, MSI-related colorectal cancer was associated with improved survival that was independent of tumor stage. MSI is also associated with Lynch syndrome.[35] In addition, gene expression profiling is useful for predicting the response of rectal adenocarcinomas to preoperative chemoradiation therapy. It can also help determine the prognosis of stages II and III rectal cancer after neoadjuvant fluorouracil-based chemoradiation therapy.[36,37]

Racial and ethnic differences in overall survival (OS) after adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer have been observed, with shorter OS for Black patients than for White patients. Factors contributing to this disparity may include tumor position, type of surgical procedure, and presence of comorbid conditions.[38]

Follow-Up After Treatment

The primary goals of postoperative surveillance programs for rectal cancer are to:[39]

- Assess the efficacy of initial therapy.

- Detect new or metachronous malignancies.

- Detect potentially curable recurrent or metastatic cancers.

Routine, periodic studies following treatment for rectal cancer may lead to earlier identification and management of recurrent disease.[39,40,41,42,43] A statistically significant survival benefit has been demonstrated for more intensive follow-up protocols in two clinical trials. A meta-analysis that combined these two trials with four others reported a statistically significant improvement in survival for patients who were intensively followed.[39,44,45]

Guidelines for surveillance after initial treatment with curative intent for colorectal cancer vary between leading U.S. and European oncology societies, and optimal surveillance strategies remain uncertain.[46,47] Large, well-designed, prospective, multi-institutional, randomized studies are required to establish an evidence-based consensus for follow-up evaluation.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

Measurement of CEA, a serum glycoprotein, is frequently used in the management and follow-up of patients with rectal cancer. A review of the use of this tumor marker for rectal cancer suggests the following:[39]

- Serum CEA testing is not a valuable screening tool for rectal cancer because of its low sensitivity and low specificity.

- Postoperative CEA testing is typically restricted to patients who are potential candidates for further intervention, as follows:

- Patients with stage II or III rectal cancer (every 2–3 months for at least 2 years after diagnosis).

- Patients with rectal cancer who would be candidates for resection of liver metastases.

In one Dutch retrospective study of total mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer, investigators found that the preoperative serum CEA level was normal in most patients with rectal cancer, and yet, serum CEA levels rose by at least 50% in patients with recurrence. The authors concluded that serial, postoperative CEA testing cannot be discarded based on a normal preoperative serum CEA level in patients with rectal cancer.[48,49]

References:

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al.: Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74 (3): 229-263, 2024.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Albano JD, Ward E, Jemal A, et al.: Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. J Natl Cancer Inst 99 (18): 1384-94, 2007.

- Kauh J, Brawley OW, Berger M: Racial disparities in colorectal cancer. Curr Probl Cancer 31 (3): 123-33, 2007 May-Jun.

- Wolpin BM, Meyerhardt JA, Mamon HJ, et al.: Adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 57 (3): 168-85, 2007 May-Jun.

- Libutti SK, Willett CG, Saltz LB: Cancer of the rectum. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 1127-41.

- Johns LE, Houlston RS: A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol 96 (10): 2992-3003, 2001.

- Imperiale TF, Juluri R, Sherer EA, et al.: A risk index for advanced neoplasia on the second surveillance colonoscopy in patients with previous adenomatous polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 80 (3): 471-8, 2014.

- Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers A, et al.: Risk of colorectal cancer after diagnosis of endometrial cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 31 (16): 2010-5, 2013.

- Srinivasan R, Yang YX, Rubin SC, et al.: Risk of colorectal cancer in women with a prior diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy. J Clin Gastroenterol 41 (3): 291-6, 2007.

- Mork ME, You YN, Ying J, et al.: High Prevalence of Hereditary Cancer Syndromes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 33 (31): 3544-9, 2015.

- Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Hannig CM, et al.: Intestinal cancer risk in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 15 (4): 576-83, 2011.

- Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, et al.: Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol 22 (9): 1958-72, 2011.

- Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E: Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 124 (10): 2406-15, 2009.

- Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Pinsky PF, et al.: Race and colorectal cancer disparities: health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (8): 538-46, 2010.

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, et al.: Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21 (5): 728-36, 2012.

- Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, et al.: Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 8 (1): e53916, 2013.

- Stein W, Farina A, Gaffney K, et al.: Characteristics of colon cancer at time of presentation. Fam Pract Res J 13 (4): 355-63, 1993.

- Majumdar SR, Fletcher RH, Evans AT: How does colorectal cancer present? Symptoms, duration, and clues to location. Am J Gastroenterol 94 (10): 3039-45, 1999.

- Compton CC, Greene FL: The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. CA Cancer J Clin 54 (6): 295-308, 2004 Nov-Dec.

- Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart AK, et al.: The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined. Ann Surg Oncol 10 (1): 65-71, 2003 Jan-Feb.

- Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al.: Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol 21 (15): 2912-9, 2003.

- Prandi M, Lionetto R, Bini A, et al.: Prognostic evaluation of stage B colon cancer patients is improved by an adequate lymphadenectomy: results of a secondary analysis of a large scale adjuvant trial. Ann Surg 235 (4): 458-63, 2002.

- Tepper JE, O'Connell MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al.: Impact of number of nodes retrieved on outcome in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 19 (1): 157-63, 2001.

- Balch GC, De Meo A, Guillem JG: Modern management of rectal cancer: a 2006 update. World J Gastroenterol 12 (20): 3186-95, 2006.

- Weiser MR, Landmann RG, Wong WD, et al.: Surgical salvage of recurrent rectal cancer after transanal excision. Dis Colon Rectum 48 (6): 1169-75, 2005.

- Fujita S, Nakanisi Y, Taniguchi H, et al.: Cancer invasion to Auerbach's plexus is an important prognostic factor in patients with pT3-pT4 colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 50 (11): 1860-6, 2007.

- Griffin MR, Bergstralh EJ, Coffey RJ, et al.: Predictors of survival after curative resection of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Cancer 60 (9): 2318-24, 1987.

- DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

- Wieder HA, Rosenberg R, Lordick F, et al.: Rectal cancer: MR imaging before neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for prediction of tumor-free circumferential resection margins and long-term survival. Radiology 243 (3): 744-51, 2007.

- Gunderson LL, Sargent DJ, Tepper JE, et al.: Impact of T and N stage and treatment on survival and relapse in adjuvant rectal cancer: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol 22 (10): 1785-96, 2004.

- Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al.: PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med 372 (26): 2509-20, 2015.

- Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, et al.: Durable Clinical Benefit With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in DNA Mismatch Repair-Deficient/Microsatellite Instability-High Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 36 (8): 773-779, 2018.

- André T, Shiu KK, Kim TW, et al.: Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability-High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med 383 (23): 2207-2218, 2020.

- Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, et al.: Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 342 (2): 69-77, 2000.

- Liersch T, Langer C, Ghadimi BM, et al.: Lymph node status and TS gene expression are prognostic markers in stage II/III rectal cancer after neoadjuvant fluorouracil-based chemoradiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 24 (25): 4062-8, 2006.

- Ghadimi BM, Grade M, Difilippantonio MJ, et al.: Effectiveness of gene expression profiling for response prediction of rectal adenocarcinomas to preoperative chemoradiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 23 (9): 1826-38, 2005.

- Dignam JJ, Ye Y, Colangelo L, et al.: Prognosis after rectal cancer in blacks and whites participating in adjuvant therapy randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 21 (3): 413-20, 2003.

- Abir F, Alva S, Longo WE, et al.: The postoperative surveillance of patients with colon cancer and rectal cancer. Am J Surg 192 (1): 100-8, 2006.

- Martin EW, Minton JP, Carey LC: CEA-directed second-look surgery in the asymptomatic patient after primary resection of colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg 202 (3): 310-7, 1985.

- Bruinvels DJ, Stiggelbout AM, Kievit J, et al.: Follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg 219 (2): 174-82, 1994.

- Lautenbach E, Forde KA, Neugut AI: Benefits of colonoscopic surveillance after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 220 (2): 206-11, 1994.

- Khoury DA, Opelka FG, Beck DE, et al.: Colon surveillance after colorectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (3): 252-6, 1996.

- Pietra N, Sarli L, Costi R, et al.: Role of follow-up in management of local recurrences of colorectal cancer: a prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum 41 (9): 1127-33, 1998.

- Secco GB, Fardelli R, Gianquinto D, et al.: Efficacy and cost of risk-adapted follow-up in patients after colorectal cancer surgery: a prospective, randomized and controlled trial. Eur J Surg Oncol 28 (4): 418-23, 2002.

- Pfister DG, Benson AB, Somerfield MR: Clinical practice. Surveillance strategies after curative treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350 (23): 2375-82, 2004.

- Li Destri G, Di Cataldo A, Puleo S: Colorectal cancer follow-up: useful or useless? Surg Oncol 15 (1): 1-12, 2006.

- Kapiteijn E, Kranenbarg EK, Steup WH, et al.: Total mesorectal excision (TME) with or without preoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of primary rectal cancer. Prospective randomised trial with standard operative and histopathological techniques. Dutch ColoRectal Cancer Group. Eur J Surg 165 (5): 410-20, 1999.

- Grossmann I, de Bock GH, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg WM, et al.: Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) measurement during follow-up for rectal carcinoma is useful even if normal levels exist before surgery. A retrospective study of CEA values in the TME trial. Eur J Surg Oncol 33 (2): 183-7, 2007.