Health Library

Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

- General Information About Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma Treatment

- Cellular Classification of Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma

- Classification and Stage Information for Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma

- Treatment Option Overview for Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma

- Treatment of Iris Melanoma

- Treatment of Ciliary Body Melanoma

- Treatment of Small Choroidal Melanoma

- Treatment of Medium and Large Choroidal Melanoma

- Treatment of Extraocular Extension and Metastatic Intraocular Melanoma

- Treatment of Recurrent Intraocular Melanoma

- Latest Updates to This Summary (12 / 19 / 2024)

- About This PDQ Summary

General Information About Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma Treatment

Incidence and Mortality

Melanoma of the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body, and choroid) is rare, but it is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults. The mean age-adjusted incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States is approximately 4.3 new cases per million people, with no clear variation by latitude. The incidence is higher in men (4.9 cases per million) than in women (3.7 cases per million).[1] The age-adjusted incidence of this cancer has remained stable since at least the early 1970s.[1,2] U.S. incidence rates are lower than the rates of other reporting countries, which vary from about 5.3 to 10.9 cases per million. Some of the variation may be the result of differences in inclusion criteria and methods of calculation.[1]

Uveal melanoma is most often diagnosed in older individuals, with a progressively rising, age-specific incidence rate that peaks near age 70 years.[3]

Host susceptibility factors associated with the development of this cancer include:[2,3,4]

- White race and ethnicity.

- Light eye color.

- Fair skin.

- The ability to tan.

In view of these susceptibility factors, numerous observational studies have attempted to explore the relationship between sunlight exposure and risk of uveal melanoma. These studies have found only weak associations or yielded contradictory results.[3] Similarly, there is no consistent evidence that occupational exposure to UV light or other agents is a risk factor for uveal melanoma.[3,5]

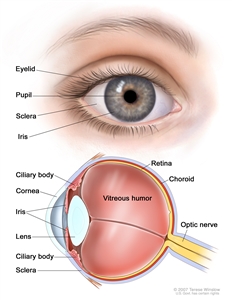

Anatomy

Uveal melanomas can arise in the anterior (iris) or the posterior (ciliary body or choroid) uveal tract.[6] Most uveal tract melanomas originate in the choroid. The ciliary body is a less common site of origin, and the iris is the least common. The comparatively low incidence of iris melanomas has been attributed to the characteristic features of these tumors; they tend to be smaller, slower growing, and relatively dormant compared with their posterior counterparts. Iris melanomas rarely metastasize.[7] Melanomas of the posterior uveal tract generally have a more malignant histological appearance; are detected later; and metastasize more frequently than iris melanomas. The typical choroidal melanoma is a brown, elevated, dome-shaped subretinal mass. The degree of pigmentation ranges from dark brown to totally amelanotic.

Most uveal melanomas are initially completely asymptomatic. As the tumor enlarges, it may cause distortion of the pupil (iris melanoma), blurred vision (ciliary body melanoma), or markedly decreased visual acuity caused by secondary retinal detachment (choroidal melanoma). Serous detachment of the retina may occur. If extensive detachment occurs, secondary angle-closure glaucoma occasionally develops. Clinically, several lesions simulate uveal melanoma, including metastatic carcinoma, posterior scleritis, and benign tumors, such as nevi and hemangiomas.[8]

Anatomy of the eye.

Diagnosis

Careful examination by an experienced clinician remains the most important test to diagnose intraocular melanoma. A small uveal melanoma cannot be distinguished from a nevus. Small uveal lesions are observed for growth before making a diagnosis of melanoma. Clinical findings that may help to identify melanoma include:[6]

- Orange pigment on the tumor surface.

- Subretinal fluid.

- Tumor thickness of more than 2 mm.

- Low internal reflectivity on ultrasound examination.

Ancillary diagnostic testing, including fluorescein angiography and ultrasonography, can be extremely valuable in establishing and confirming the diagnosis.[9] In a large, retrospective, single-center series of 2,514 consecutive patients with choroidal nevi, the progression rate to melanoma was 8.6% at 5 years, 12.8% at 10 years, and 17.3% at 15 years.[10]

Prognostic Factors

Several factors influence prognosis. The most important factors include:

- Cell type. For more information, see the Cellular Classification of Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma section.

- Tumor size.

- Location of the anterior margin of the tumor.

- Degree of ciliary body involvement.

- Extraocular extension.

Several additional microscopic features can affect the prognosis of intraocular melanoma, including:

- Mitotic activity.

- Lymphocytic infiltration.

- Fibrovascular loops (possibly).

Cell type is the most commonly used predictor of outcome following enucleation. Patients with spindle-A cell melanomas have the best prognosis and patients with epithelioid cell melanomas have the least favorable prognosis.[1,4,9] Nevertheless, most tumors have an admixture of cell types, and there is no clear consensus regarding the proportion of epithelioid cells that constitutes designation of a tumor as mixed or epithelioid.[6]

Extraocular extension, recurrence, and metastasis are associated with an extremely poor prognosis, and long-term survival cannot be expected for patients with these features.[11] The 5-year mortality rate for patients with metastasis from ciliary body or choroidal melanoma is approximately 30%, compared with a rate of 2% to 3% for patients with iris melanomas.[12]

References:

- Singh AD, Topham A: Incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States: 1973-1997. Ophthalmology 110 (5): 956-61, 2003.

- Inskip PD, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF: Trends in the incidence of ocular melanoma in the United States, 1974-1998. Cancer Causes Control 14 (3): 251-7, 2003.

- Singh AD, Bergman L, Seregard S: Uveal melanoma: epidemiologic aspects. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 18 (1): 75-84, viii, 2005.

- Weis E, Shah CP, Lajous M, et al.: The association between host susceptibility factors and uveal melanoma: a meta-analysis. Arch Ophthalmol 124 (1): 54-60, 2006.

- Harris RB, Griffith K, Moon TE: Trends in the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancers in southeastern Arizona, 1985-1996. J Am Acad Dermatol 45 (4): 528-36, 2001.

- Uveal melanoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 805–17.

- Yap-Veloso MI, Simmons RB, Simmons RJ: Iris melanomas: diagnosis and management. Int Ophthalmol Clin 37 (4): 87-100, 1997 Fall.

- Eye and ocular adnexa. In: Rosai J: Ackerman's Surgical Pathology. 8th ed. Mosby, 1996, pp 2449-2508.

- Albert DM, Kulkarni AD: Intraocular melanoma. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 2090-8.

- Shields CL, Furuta M, Berman EL, et al.: Choroidal nevus transformation into melanoma: analysis of 2514 consecutive cases. Arch Ophthalmol 127 (8): 981-7, 2009.

- Gragoudas ES, Egan KM, Seddon JM, et al.: Survival of patients with metastases from uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology 98 (3): 383-9; discussion 390, 1991.

- Introduction to melanocytic tumors of the uvea. In: Shields JA, Shields CL: Intraocular Tumors: A Text and Atlas. Saunders, 1992, pp 45-59.