Health Library

Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

- General Information About Colon Cancer

- Cellular Classification of Colon Cancer

- Stage Information for Colon Cancer

- Treatment Option Overview for Colon Cancer

- Treatment of Stage 0 Colon Cancer

- Treatment of Stage I Colon Cancer

- Treatment of Stage II Colon Cancer

- Treatment of Stage III Colon Cancer

- Treatment of Stage IV and Recurrent Colon Cancer

- Latest Updates to This Summary (02 / 12 / 2025)

- About This PDQ Summary

General Information About Colon Cancer

Cancer of the colon is a highly treatable and often curable disease when localized to the bowel. Surgery is the primary form of treatment and results in cure in approximately 50% of patients. However, recurrence following surgery is a major problem and is often the ultimate cause of death.

Incidence and Mortality

Worldwide, colorectal cancer is the third most common form of cancer. In 2022, there were an estimated 1.93 million new cases of colorectal cancer and 903,859 deaths.[1]

Estimated new cases and deaths from colon and rectal cancer in the United States in 2025:[2]

- New cases of colon cancer: 107,320.

- New cases of rectal cancer: 46,950.

- Deaths: 52,900 (colon and rectal cancers combined).

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors can occur in the colon. For more information, see Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Treatment.

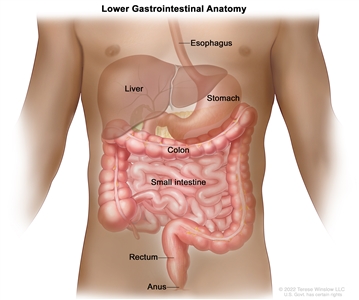

Anatomy

Anatomy of the lower gastrointestinal (digestive) system.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for colorectal cancer include the following:

- Family history of colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative.[3]

- Personal history of colorectal adenomas, colorectal cancer, or ovarian cancer.[4,5,6]

- Hereditary conditions, including familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer [HNPCC]).[7]

- Personal history of long-standing chronic ulcerative colitis or Crohn colitis.[8]

- Excessive alcohol use.[9]

- Cigarette smoking.[10]

- Race and ethnicity: African American.[11,12]

- Obesity.[13]

Screening

Screening for colon cancer should be a part of routine care for all adults aged 50 years and older, especially for those with first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer. This recommendation is based on the frequency of the disease, ability to identify high-risk groups, slow growth of primary lesions, better survival of patients with early-stage lesions, and relative simplicity and accuracy of screening tests. For more information, see Colorectal Cancer Screening.

Prognostic Factors

The prognosis of patients with colon cancer is clearly related to:

- The degree of penetration of the tumor through the bowel wall.

- The presence or absence of nodal involvement.

- The presence or absence of distant metastases.

These three characteristics form the basis for all staging systems developed for this disease.

Other prognostic factors for colon cancer include:

- Bowel obstruction and bowel perforation are indicators of poor prognosis.[14]

- Elevated pretreatment serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) have a negative prognostic significance.[15]

Many other prognostic markers have been evaluated retrospectively for patients with colon cancer, though most, including allelic loss of chromosome 18q or thymidylate synthase expression, have not been prospectively validated.[16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] Microsatellite instability, also associated with HNPCC, has been associated with improved survival independent of tumor stage in a population-based series of 607 patients younger than 50 years with colorectal cancer.[26] Patients with HNPCC reportedly have better prognoses in stage-stratified survival analysis than patients with sporadic colorectal cancer, but the retrospective nature of the studies and possibility of selection factors make this observation difficult to interpret.[27]

Treatment decisions depend on factors such as physician and patient preferences and the stage of the disease, rather than the age of the patient.[28,29,30]

Racial differences in overall survival (OS) after adjuvant therapy have been observed, without differences in disease-free survival, suggesting that comorbid conditions play a role in survival outcome in different patient populations.[31]

Follow-Up and Survivorship

Limited data and no high-level evidence are available to guide patients and physicians about surveillance and management of patients after surgical resection and adjuvant therapy. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend specific surveillance and follow-up strategies.[32,33]

Following treatment of colon cancer, periodic evaluations may lead to the earlier identification and management of recurrent disease.[34,35,36,37] This monitoring has limited effect on overall mortality, as few localized, potentially curable metastases are found in patients with recurrent colon cancer. To date, no large-scale randomized trials have documented an OS benefit for standard, postoperative monitoring programs.[38,39,40,41,42]

CEA is a serum glycoprotein frequently used in the management of patients with colon cancer. A review of the use of this tumor marker suggests:[43]

- A CEA level is not a valuable screening test for colorectal cancer because of the large number of false-positive and false-negative reports.

- Postoperative CEA testing should be restricted to patients who would be candidates for resection of liver or lung metastases.

- Routine use of CEA levels alone for monitoring response to treatment is not recommended.

The optimal regimen and frequency of follow-up examinations are not well defined because the impact on patient survival is not clear and the quality of data is poor.[40,41,42]

Factors Associated With Recurrence

Diet and exercise

Although cohort studies have suggested that a diet or exercise regimen may improve outcomes, no prospective randomized trials have confirmed these findings. The cohort studies contained multiple opportunities for unintended bias, and caution is needed when using the data from them.

Two prospective observational studies were performed with patients enrolled in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B CALGB-89803 trial (NCT00003835), an adjuvant chemotherapy trial for patients with stage III colon cancer.[44,45] In this trial, patients in the lowest quintile of the Western dietary pattern, compared with those patients in the highest quintile, experienced an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for disease-free survival of 3.25 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.04–5.19; P < .001) and an OS of 2.32 (95% CI, 1.36–3.96; P < .001). Additionally, stage III colon cancer patients in the highest quintile of dietary glycemic load experienced an adjusted HR for OS of 1.76 (95% CI, 1.22–2.54; P < .001), compared with those in the lowest quintile. Subsequently, in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort, among 2,315 participants diagnosed with colorectal cancer, the degree of red and processed meat intake before diagnosis was associated with a higher risk of death (relative risk [RR], 1.29; 95% CI, 1.05–1.59; P = .03), but red meat consumption after diagnosis was not associated with overall mortality.[46][Level of evidence C1]

A meta-analysis of seven prospective cohort studies evaluating physical activity before and after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer demonstrated that patients who participated in any amount of physical activity before diagnosis had an RR of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.65–0.87; P < .001) for colorectal cancer-specific mortality, compared with patients who did not participate in any physical activity.[47] Patients who participated in a high amount of physical activity (vs. a low amount) before diagnosis had an RR of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.56–0.87; P = .002). Patients who participated in any physical activity (compared with no activity) after diagnosis had an RR of 0.74 (95% CI, 0.58–0.95; P = .02) for colorectal cancer-specific mortality. Those who participated in a high amount of physical activity (vs. a low amount) after diagnosis had an RR of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.47–0.92; P = .01).[47][Level of evidence C1]

Aspirin

A prospective cohort study examined the use of aspirin after a colorectal cancer diagnosis.[48] Regular users of aspirin after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer experienced an HRcolon cancer–specific mortality of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.53–0.95) and an HRoverall mortality of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.65–0.97).[48][Level of evidence C1] One study evaluated 964 patients with rectal or colon cancer from the Nurse's Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study.[49] Among patients with colorectal cancer and PI3K variants, regular use of aspirin was associated with an HRdeath from any cause of 0.54 (95% CI, 0.31–0.94; P = .01)[49][Level of evidence C1]

References:

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al.: Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74 (3): 229-263, 2024.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Johns LE, Houlston RS: A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol 96 (10): 2992-3003, 2001.

- Imperiale TF, Juluri R, Sherer EA, et al.: A risk index for advanced neoplasia on the second surveillance colonoscopy in patients with previous adenomatous polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 80 (3): 471-8, 2014.

- Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers A, et al.: Risk of colorectal cancer after diagnosis of endometrial cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 31 (16): 2010-5, 2013.

- Srinivasan R, Yang YX, Rubin SC, et al.: Risk of colorectal cancer in women with a prior diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy. J Clin Gastroenterol 41 (3): 291-6, 2007.

- Mork ME, You YN, Ying J, et al.: High Prevalence of Hereditary Cancer Syndromes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 33 (31): 3544-9, 2015.

- Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Hannig CM, et al.: Intestinal cancer risk in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 15 (4): 576-83, 2011.

- Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, et al.: Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol 22 (9): 1958-72, 2011.

- Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E: Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 124 (10): 2406-15, 2009.

- Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Pinsky PF, et al.: Race and colorectal cancer disparities: health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (8): 538-46, 2010.

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, et al.: Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21 (5): 728-36, 2012.

- Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, et al.: Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 8 (1): e53916, 2013.

- Steinberg SM, Barkin JS, Kaplan RS, et al.: Prognostic indicators of colon tumors. The Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group experience. Cancer 57 (9): 1866-70, 1986.

- Filella X, Molina R, Grau JJ, et al.: Prognostic value of CA 19.9 levels in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 216 (1): 55-9, 1992.

- McLeod HL, Murray GI: Tumour markers of prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 79 (2): 191-203, 1999.

- Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, et al.: Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 331 (4): 213-21, 1994.

- Lanza G, Matteuzzi M, Gafá R, et al.: Chromosome 18q allelic loss and prognosis in stage II and III colon cancer. Int J Cancer 79 (4): 390-5, 1998.

- Griffin MR, Bergstralh EJ, Coffey RJ, et al.: Predictors of survival after curative resection of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Cancer 60 (9): 2318-24, 1987.

- Johnston PG, Fisher ER, Rockette HE, et al.: The role of thymidylate synthase expression in prognosis and outcome of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 12 (12): 2640-7, 1994.

- Shibata D, Reale MA, Lavin P, et al.: The DCC protein and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 335 (23): 1727-32, 1996.

- Bauer KD, Lincoln ST, Vera-Roman JM, et al.: Prognostic implications of proliferative activity and DNA aneuploidy in colonic adenocarcinomas. Lab Invest 57 (3): 329-35, 1987.

- Bauer KD, Bagwell CB, Giaretti W, et al.: Consensus review of the clinical utility of DNA flow cytometry in colorectal cancer. Cytometry 14 (5): 486-91, 1993.

- Sun XF, Carstensen JM, Zhang H, et al.: Prognostic significance of cytoplasmic p53 oncoprotein in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Lancet 340 (8832): 1369-73, 1992.

- Roth JA: p53 prognostication: paradigm or paradox? Clin Cancer Res 5 (11): 3345, 1999.

- Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, et al.: Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 342 (2): 69-77, 2000.

- Watson P, Lin KM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, et al.: Colorectal carcinoma survival among hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma family members. Cancer 83 (2): 259-66, 1998.

- Iwashyna TJ, Lamont EB: Effectiveness of adjuvant fluorouracil in clinical practice: a population-based cohort study of elderly patients with stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 20 (19): 3992-8, 2002.

- Chiara S, Nobile MT, Vincenti M, et al.: Advanced colorectal cancer in the elderly: results of consecutive trials with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 42 (4): 336-40, 1998.

- Popescu RA, Norman A, Ross PJ, et al.: Adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in patients 70 years or older. J Clin Oncol 17 (8): 2412-8, 1999.

- Dignam JJ, Colangelo L, Tian W, et al.: Outcomes among African-Americans and Caucasians in colon cancer adjuvant therapy trials: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project. J Natl Cancer Inst 91 (22): 1933-40, 1999.

- Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, et al.: Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol 31 (35): 4465-70, 2013.

- Benson AB, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, et al.: Localized colon cancer, version 3.2013: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 11 (5): 519-28, 2013.

- Martin EW, Minton JP, Carey LC: CEA-directed second-look surgery in the asymptomatic patient after primary resection of colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg 202 (3): 310-7, 1985.

- Bruinvels DJ, Stiggelbout AM, Kievit J, et al.: Follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg 219 (2): 174-82, 1994.

- Lautenbach E, Forde KA, Neugut AI: Benefits of colonoscopic surveillance after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 220 (2): 206-11, 1994.

- Khoury DA, Opelka FG, Beck DE, et al.: Colon surveillance after colorectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (3): 252-6, 1996.

- Safi F, Link KH, Beger HG: Is follow-up of colorectal cancer patients worthwhile? Dis Colon Rectum 36 (7): 636-43; discussion 643-4, 1993.

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al.: An evaluation of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test for monitoring patients with resected colon cancer. JAMA 270 (8): 943-7, 1993.

- Rosen M, Chan L, Beart RW, et al.: Follow-up of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 41 (9): 1116-26, 1998.

- Desch CE, Benson AB, Smith TJ, et al.: Recommended colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 17 (4): 1312, 1999.

- Benson AB, Desch CE, Flynn PJ, et al.: 2000 update of American Society of Clinical Oncology colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines. J Clin Oncol 18 (20): 3586-8, 2000.

- Clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer. Adopted on May 17, 1996 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 14 (10): 2843-77, 1996.

- Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al.: Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA 298 (7): 754-64, 2007.

- Meyerhardt JA, Sato K, Niedzwiecki D, et al.: Dietary glycemic load and cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J Natl Cancer Inst 104 (22): 1702-11, 2012.

- McCullough ML, Gapstur SM, Shah R, et al.: Association between red and processed meat intake and mortality among colorectal cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 31 (22): 2773-82, 2013.

- Je Y, Jeon JY, Giovannucci EL, et al.: Association between physical activity and mortality in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer 133 (8): 1905-13, 2013.

- Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS: Aspirin use and survival after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. JAMA 302 (6): 649-58, 2009.

- Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, et al.: Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med 367 (17): 1596-606, 2012.