When discussing hip fractures, most people tend to think of proximal femur fractures. However, acetabular fractures are becoming more common among people 60 years and older, and timing of surgery to repair the injury is critical in ensuring optimal recovery and patient outcomes. Nicholas C. Danford, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia, discusses his recent study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons assessing how the time from hospital admission to surgery impacts postoperative complications and greater mortality.

Research Goals

Because there has been less research done around the timing for treatment of acetabular fractures, there are no guidelines to follow for how soon to operate when a patient presents to the emergency room with one. We wanted to determine whether there is an association between that timeline and postoperative complications and mortality for older patients who undergo surgical fixation or arthroplasty. We believed that inpatient complications and mortality would increase with the length of time.

Research Methods

The study assessed National Trauma Bank data between 2016 and 2018 of patients with acetabular fractures requiring open reduction and internal fixation, percutaneous acetabular fixation, and/or total hip arthroplasty. This databank is well-vetted and maintained by the Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons and contains more than 7.5 million records from over 900 trauma centers across the U.S., making it the largest repository of trauma data in the world. There were 6,036 patients ranging in age 64 to 76 years who met the inclusion criteria.

Patients were also stratified using several factors including the modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (mCCI), which essentially tells us how sick each patient is and what their preoperative activity level is like. Each patient can be so vastly physiologically different. You can have a 65-year-old with end-stage renal disease or other serious medical issues, and a 65-year-old who just played their fourth round of golf of the week. This is why subgroup analysis that takes comorbidities into account is important. Preoperative activity level is also much more important of a factor than bone density because these two types of patients can actually have similar bone densities.

Key Findings

- A decrease in time between admission and surgery was associated with fewer inpatient complications.

- The possibility of a complication increased by 7% for each additional day between hospital admission and surgery.

- A relatively low proportion of patients (just under 5%) experienced complications if they underwent surgery within the first two days after admission.

- Comorbidities and age were markedly associated with mortality and complications, a finding reflected in other literature. However, inpatient mortality was not associated with time to surgery.

- Time to surgery may be a modifiable risk factor of inpatient complications.

Generally, we found that delay to surgery and the complication rate is an association, not a causation. The 7% finding was the most significant finding of the study, but it has to be understood in the context of how sick each patient is based on the mCCI. Patients who are sicker are more likely to be delayed going to the OR because they may need to undergo a transfusion, an echo, or a DVT study, or have extensive discussions about the wisdom of having surgery in light of their medical status. There are a lot of confounding factors at play.

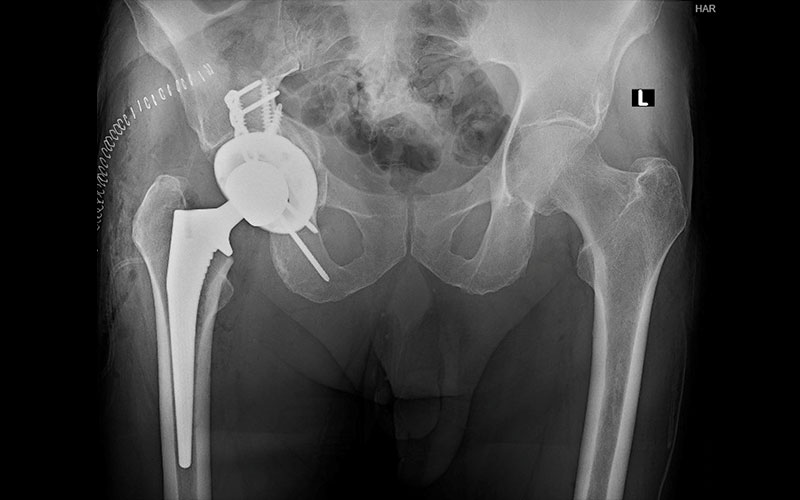

Patient who underwent surgical treatment of a geriatric acetabular fracture.

Implications

Assuming that a patient is healthy enough for surgery, I believe there are a number of reasons to optimize the timing of surgery for older patients. These fractures can lead to prolonged hospital stays, perioperative complications, 30-day mortality between 2% and 7%, and one-year mortality rates as high as 20%, which makes it critical to perform surgery as early as medically advised. Earlier postoperative mobilization is also certainly a goal of surgery, within the parameters of the patient’s comorbidities and the type of surgery, because of the risks associated with being bed-bound, like pressure ulcers, clots, sarcopenia muscle loss, and much more.

Of course, individualized treatment plans based on all the confounding factors is key, and more research needs to be done to determine how time to surgery affects longer-term mortality in older patients. But I have faith in this analysis, and studies like this, combined with clinical experience, can help doctors with the complexities of surgical decision-making.