Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a condition that causes the blood vessels of the brain to become fragile over time, is a relatively common disease in the elderly that can lead to devastating intracerebral hemorrhage. Inflammatory CAA is a rare complication of CAA that can lead to disability and cognitive decline if left undetected and untreated. NewYork-Presbyterian/

Samuel Bruce, MD

"We don't have great tools for catching this disease early or managing it before it causes symptoms," explains lead author Samuel Bruce, MD, a neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/

In patients with general CAA, amyloid protein deposits build up over many years in the walls of the cerebral blood vessels. The protein weakens the blood vessel walls until eventually, the walls become very fragile and bleed. The disease is found in people over age 50, and the risk of developing it increases with advancing age.

Inflammatory CAA is an autoimmune response to the amyloid deposits building up in arterial walls. It can cause cognitive decline, headaches, seizures, and debilitating focal deficits. It can happen earlier in life than non-inflammatory CAA, affecting people age 40 and older.

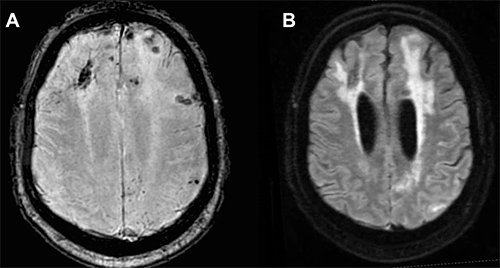

MRI scans of a patient with CAA.

(Image courtesy of Current Treatment Options in Neurology).

While there is no known cause of inflammatory CAA, people who have the APOE4 genotype — the same one linked to Alzheimer's disease — have an increased risk of the disease. Researchers are continuing to explore the role of APOE4 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory CAA.

Because this disease is thought to be relatively rare, it is difficult to study at the population level. Consortiums, such as the Inflammatory Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Alzheimer’s disease Biomarkers International Network (iCAβ), have been gathering multicenter data to gain more insights into its pathogenesis and optimal management. Their discovery of elevated levels of antibodies against amyloid in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of inflammatory CAA patients supports the possibility that the disease may be related to the clinically and radiographically similar entity known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), a common complication of newly approved immunotherapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Increasing use of immunotherapies for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease may offer opportunities for researchers to learn more about both ARIA and inflammatory CAA.

Learning how to detect inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy earlier could lead to prompt intervention and reduce the risk of long-term disability, cognitive impairment, and possibly cerebral hemorrhage.

— Dr. Samuel Bruce

Making the Diagnosis

"Inflammatory CAA can cause clinical changes that present well before a hemorrhage," explains Dr. Bruce. Those changes may include:

- Cognitive impairment and dementia

- Transient focal neurological episodes, such as aphasia, visual disturbances, and sensory changes — also called "amyloid spells"

- Headaches

- Seizures

MRI is essential to make a diagnosis and contrast enhancement is helpful but not required. MRI scans generated using fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequencing show white matter hyperintense lesions extending to the immediately subcortical white matter and one or more of the following hemorrhagic lesions:

- Cerebral macrohemorrhage

- Cerebral microhemorrhage

- Cortical superficial siderosis

Brain biopsy is the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis, but because it is invasive, it is often reserved for patients who do not respond well to CAA therapies.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis (CSF) may also be helpful to rule out other diagnoses. Studies by iCAβ have reported that antibodies against amyloid protein in the CSF are elevated early on in symptomatic disease and diminish with immunosuppressive treatment, but measurement of these antibodies is still experimental and not yet used routinely in clinical practice.

Inflammatory CAA features should be distinguished from the following diseases:

- Any inflammatory or infectious condition affecting the central nervous system

- Leptomeningeal disease and cancer

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), which tends to affect the back of the brain in the same way as inflammatory CAA

Optimizing the Treatment of Inflammatory CAA

Because inflammatory CAA is an autoimmune disease, treating it requires immunosuppressant medications. Patients generally begin with three to five days of high-dose steroid therapy, such as intravenous methylprednisolone, followed by 60 mg of oral prednisone daily with a slow taper over six months.

The patient is re-evaluated at six months with a clinical assessment to evaluate symptoms such as headaches and seizures, cognition, and level of functioning. Repeat MRI is indicated to determine if areas of brain inflammation lessened, remained stable, or worsened. Patients with severe or refractory disease may need additional treatment with cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, azathioprine, and intravenous immunoglobulin, with the dose and duration guided by therapeutic response.

Despite this regimen, there is a lack of consensus regarding the treatment of inflammatory CAA. "We need to gather data on the optimal duration of immunosuppression, the optimal agents, and the long-term outcomes of therapy," says Dr. Bruce. "Immunosuppressants have side effects, so we need to gauge their long-term use in people with cancer and other diseases that may raise their risk of infection while on treatment." The identification of effective disease-modifying therapies may prevent inflammatory CAA from progressing.

Doctors should maintain a high index of suspicion for inflammatory CAA in people with new acute and subacute cognitive changes, headaches, seizures, and focal deficits.

— Dr. Samuel Bruce

When to Refer a Patient

Because the symptoms and presentation of inflammatory CAA mimic those of other inflammatory central nervous system disorders, its nonspecific and vague symptoms may lead to an underdiagnosis of the disease. Dr. Bruce suggests that there should be a "high index of suspicion" for inflammatory CAA in patients over age 40 who present with acute or subacute cognitive changes or new neurologic symptoms. This is especially important for anyone with a history of lobar intracerebral hemorrhage, new seizures, or new headaches. Doctors should refer these patients to a neurologist for evaluation, and neurologists are encouraged to refer patients for MRI scanning using FLAIR sequencing.

"I have a feeling that inflammatory CAA is not a diagnosis that a lot of neurologists have been on the lookout for," Dr. Bruce surmises. "But we do need to be on the lookout for it."