“Intramedullary spinal cord tumors, which are located inside the substance of the spinal cord, are rare and surgery to remove them is always technically challenging and very high risk to perform,” says Paul C. McCormick, MD, Director of the Spine Hospital of the Neurological Institute of New York at NewYork-Presbyterian/

Dr. Paul McCormick

Dr. McCormick, who is also the Gallen Professor of Neurological Surgery at Columbia, is among a select group of spinal neurosurgeons specializing in intramedullary spinal cord tumors. As such he has operated on patients from cities as far away as Seattle and countries around the world who come to NewYork-Presbyterian/

Early on in his career, Dr. McCormick, Bennett M. Stein, MD, then Director of Columbia’s Department of Neurosurgery, and two of their colleagues developed an innovative scale to stratify and characterize patients with these tumors by their neurologic function noting that patient outcomes are often related to their level of function prior to surgery. In 1990, they wrote about this scale in their article on operative removal of intramedullary ependymomas of the spinal cord published in the Journal of Neurosurgery. Such was its utility for spinal neurosurgeons that, subsequently, the scale, which was then named for Dr. McCormick, was widely adopted and remains in use to this day. The McCormick Scale serves as a clinical/functional classification tool to evaluate patients who present with intramedullary spinal cord tumors in order to categorize a patient's mobility and sensory status.

“Over the years, our proficiency has evolved significantly, not just in terms of judgment, but also in the evolution of surgical techniques and technology,” says Dr. McCormick. “In particular we have access to extraordinary diagnostic imaging that has led to earlier diagnosis of these tumors, which enables us to achieve a better definition of the tumor’s location and characterization. An earlier diagnosis means the tumor will be smaller with less edema, and the patient will have a higher level of function, which are all positive reflectors of a patient's outcome after surgery.”

However, Dr. McCormick notes that more sensitive imaging has also given rise to a few dilemmas. Earlier diagnosis of these tumors also has led to the identification of incidental or asymptomatic tumors raising the question of when do you proceed to surgery…at diagnosis or do you wait for symptoms to occur?

“We know that postoperative function is correlated with preoperative function, therefore the better that patients are going into surgery, the better they are following surgery,” says Dr. McCormick. “A patient’s preoperative deficits will remain and there may be the addition of proprioceptive deficits related to the surgery. We don’t operate on asymptomatic patients, but we don’t wait until they become functionally limited or disabled before we operate. That’s the needle we try to thread in terms of selection of patients and timing of the surgery.”

“Another consequence of advanced imaging is that the sensitivity has surpassed the specificity, and we frequently have to differentiate intramedullary lesions from non-neoplastic, non-surgical conditions, primarily multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, and sarcoidosis,” adds Dr. McCormick. “In most cases, you can distinguish the patient with a tumor from the patient with a medical myelopathy based on the acute onset of the medical myelopathy, which is the substantial deficit that patients usually have. They have little or no spinal cord expansion and there is generally white matter involvement. A myelotomy for biopsy will only indicate non-specific inflammation and does not indicate a diagnosis or direct treatment beyond steroids or an immunosuppressant.”

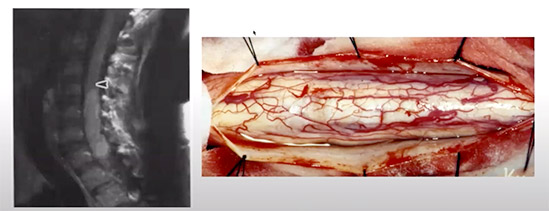

“We have also refined and advanced the techniques enabling us to reduce risk and amplify the outcomes in terms of preserving the patient’s function and limiting any residual tumor from recurring,” adds Dr. McCormick. “With real-time observation and three-dimensional imaging, we can pinpoint the tumor, visualize the surrounding spinal cord, and better define the margins.”

“It is remarkable that so many of these intramedullary tumors, especially ependymomas, still remain a surgical disease,” adds Justin A. Neira, MD, a neurological spine surgeon specializing in spinal cord injury, metastatic spinal oncology, and spinal cord tumor research at NewYork-Presbyterian/

Dr. Justin Neira

“For the most part, these operations are scripted in a broad sense, but there are variables that can present during the surgery that you can't always predict in advance and need to react in real-time to address them,” says Dr. McCormick. “And that's where the experience comes from – learning how to navigate around the unexpected but still reach your endpoint. Technology has fundamentally and qualitatively transformed how we operate. Intraoperative neuro-monitoring has made the surgery safer and intraoperative ultrasound provides guidance on how the surgery is progressing, but these are adjuvant tools for the surgeon. For me, the morbidity is at the interface between the tumor and the surrounding spinal cord. When you are at the point of extracting that tumor from the spinal cord or off of a nerve, there is no tool yet available that can supersede the surgeon’s technical know-how and judgment. For now and the foreseeable future, treating intramedullary tumors is about earlier diagnosis, appropriate surgery, and optimizing the technology that we currently do have.”

A Case in Point

Dr. McCormick describes recently being called into a surgery of a colleague operating on a brain tumor that originated in the brain stem but traveled down into the spinal cord. “When he saw that the tumor had extended beyond the brain stem, he asked me if I would help with the operation. He was astounded, noting, ‘I had no idea this could be done. These are the type of tumors you can't take out of the brain stem and you came in and took it out of the spinal cord and just followed it up to the brain stem, and took it out there. And it's gone. This patient is probably going to be cured.’”

“I've just been down that road so many times,” says Dr. McCormick. “I realized that we have one chance for this young adult patient in his thirties to do well so we were going to have to push the envelope a little bit. But you only know how much you can push based on experience that enables you to best define the margins. To me, when it comes to intramedullary tumors, you can have all the advanced surgical and imaging technology in the world, but when the rubber hits the road and you are detaching that tumor from the spinal cord, that just takes time, it takes patience, and it takes knowing the tolerance of the spinal cord. Because I've done so many of them, I've just internalized that. I'm not saying I'm perfect, or I get the outcome I want in every patient, but there’s just no replacement for experience.”

Dr. McCormick notes that his own proficiency is a product of the leadership over the years of the Department of Neurological Surgery at Columbia, supporting the neurosurgical faculty to develop a particular subspecialty field of concentration that will enable them to be counted among the best in the world.

For Dr. McCormick it goes beyond the surgical acumen he’s acquired. “I’m doing an intramedullary tumor tomorrow, and I’m going to develop a relationship with this patient. I’m going to feel very close to him in terms of did I make his life better? Have I made a difference in his life? That is what’s important and meaningful to me.”

Surgical Considerations for Ependymomas

According to the Collaborative Ependymoma Research Network (CERN) Foundation, approximately 1,100 adults are diagnosed with ependymomas each year. While nearly 22 in 100,000 people have primary central nervous system tumors, ependymomas make up less than 2 percent of adult diagnoses.

“While they are rare tumors, ependymomas are by far the most common tumors that we encounter in the intramedullary space in the adult population,” says Dr. McCormick. “The vast majority of these intramedullary tumors are uncapsulated, benign, and fairly slow growing. They do exhibit some variability in biology and the growth rate can change from person to person, but they rarely show progressive anaplasia as they do in the cranial space. What we’ve learned over the years is surgery is the primary if not only effective treatment option for the preponderance of intramedullary tumors. So you want to optimize, if you can, the surgical exposure, the techniques, and the technology that we have to make it as safe and as effective as possible.”

(Left) MRI indicating large intramedullary ependymoma (Right) Intraoperative image of the exposed tumor showing the dorsal root entry zone on either side of the midline (Courtesy of Dr. Paul McCormick)

“In the case of ependymomas, especially certain types – papillary, intramedullary, standard, and non-atypical ependymomas – surgery is curative if we can completely resect them safely without damaging any functioning nervous tissue,” says Dr. Neira. “This is where the nuance comes in – achieving a surgical cure while making this delicate surgery as safe as possible for patients and preventing the activation of an inflammatory cascade that down the line may cause a more difficult recovery.”

Dr. Neira is particularly interested in pursuing research in a number of areas that could improve the safety profile of these surgeries, including inflammatory cascades, use of neuroprotective medications in advance of surgery, and nuances among ependymoma tumors that occur on the cervical spine versus the thoracic spine versus the conus. He will be tapping into the data available from the voluminous series of patients accumulated during Dr. McCormick’s tenure to identify and characterize these differences, isolate the types of ependymomas that are more likely to recur and which may need radiation based on their location, and how much of the tumor can be removed before additional treatment is needed.

“We finally have enough data to better understand these tumors and facilitate surgical decisions and the continued care of patients,” says Dr. Neira. “Taking a look back at the last three decades of Dr. McCormick’s amazing spine tumor practice will provide us with information on how to better tailor surgery to each individual patient. Moving forward, we plan to sequence these tumor cells and identify the mutation that causes a certain spinal cord tumor to occur in the cervical spine versus the thoracic spine. Decades ago, there was no differentiation made in glioblastomas and now we know there are multiple subtypes that are associated with different prognoses. This has not yet occurred for these spinal cord tumors because they are so rare, but we have the unique opportunity because of our volume to start figuring this out.”

Dr. McCormick notes that the Columbia team has recently submitted a paper for publication on a study of myxopapillary ependymoma – a fairly rare, very complicated heterogeneous tumor that occurs in the lowest part of the spinal cord. The study involved long-term follow-up of 56 patients – one of the largest series in the United States. “We expect this to be a landmark paper as our research has demonstrated how these tumors can be stratified according to their size, location, margins, and how well developed their capsule is,” says Dr. McCormick.

Columbia Neurosurgery: An Enduring Legacy of Expertise and Training

The country’s first spinal operation for an intramedullary spinal cord tumor was performed on a female patient at Columbia’s Neurological Institute of New York by Charles Elsberg, MD, a pioneer of spine surgery and the first Chairman of Neurological Surgery at Columbia. Dr. Elsberg, who established the first such service in New York City, led the department from 1909 to 1937.

Dr. McCormick joined the neurosurgical faculty of the Neurological Institute, where he also trained, some 30 years ago. At that time, he was the first neurosurgeon to dedicate his practice entirely to the treatment of patients with spinal disorders and has since performed nearly 7,000 spinal procedures on patients from here and abroad and garnered world-renowned prominence as a spinal neurosurgeon.

Dr. Neira is fresh out of neurosurgical residency training at NewYork-Presbyterian/

Dr. Neira counts himself among the very fortunate to have trained under the tutelage of Dr. McCormick, who shared the same sentiment about his own mentor, Bennett M. Stein, MD, a former Director of Columbia’s Department of Neurosurgery and one of the world’s experts in spinal cord tumors.

“The Neurological Institute has always had an interest in being leaders in this area and passing the baton to the next generation,” says Dr. McCormick. “Dr. Stein took me under his wing to say, ‘You are the heir apparent. You are the next generation of neurological spine surgeons.’ This is the same relationship I have developed with Justin, who’s not only a superb technical surgeon, he has the right mentality for this type of surgery. There's a certain stress associated with performing these complex procedures. You have to be able and willing to spend all day in an operating room and have the patience to proceed millimeter by millimeter. He has that aptitude, and he also has the skillset. I expect that Justin will carry on this legacy.”

“Dr. McCormick basically wrote the book on how to do spine tumor surgeries and establishing a standard of care to treat these patients,” says Dr. Neira. “He is the world’s expert in this field, and he carries with him a huge amount of institutional knowledge and expertise that I, over the years, have benefited from. Ideally, over time, I would like to follow in his footsteps, helping patients with intradural, extradural, and metastatic spinal tumors and transferring the knowledge and skills I have gained and will continue to build on to the next generation.”