The treatment of Alzheimer’s disease has changed drastically in recent years. As such, it’s become increasingly more common for patients to undergo positron emission tomography (PET) scanning to diagnose and stage early Alzheimer’s — but access to scanners as well as technological limitations have made getting high-resolution brain imaging difficult for many patients.

A team at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine is working to address these challenges by developing a new type of PET scanner. Through a $6.2 million, five-year grant from the National Institute on Aging, Amir H. Goldan, Ph.D., an electrical engineer and director of the X-ray and Emission Imaging Lab at Weill Cornell Medicine, and neuroradiologist Gloria Chiang, M.D., director of the Brain Health Imaging Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine, are leading the effort to develop a portable upright brain PET scanner that can detect the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease at the highest resolution ever accomplished.

Below, Dr. Chiang and Dr. Goldan discuss the difficulties in obtaining quality brain imaging for Alzheimer’s disease, and how this new technology could address these problems and help detect cognitive impairment earlier than ever before.

One of the biggest challenges in brain PET imaging is getting high-resolution images of the smaller parts of the brain where tau proteins deposit in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s.

— Dr. Gloria Chiang

Current Challenges of Brain Imaging

Dr. Chiang: One of the biggest challenges in brain PET imaging is getting high-resolution images of the smaller parts of the brains, like the locus coeruleus and the transentorhinal cortex. These regions are important, particularly for Alzheimer’s diagnosis, because these are where tau proteins can deposit in the earliest stages of the disease, even before people have cognitive symptoms. Traditionally, PET scans have been the only way to identify tau protein deposition but come with significant limitations.

Dr. Goldan: It is also well known that PET has suboptimal spatial resolution among imaging technologies, significantly lower than CT and MRI. The norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonergic systems, which are all significantly impacted by Alzheimer’s, originate from very small regions of the brain that we are not able to see clearly on current PET scans due to the low resolution.

Currently, we use Braak staging with PET scans to measure the accumulation of tau neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in different regions of the brain. In Alzheimer's disease, tau accumulation begins in the transentorhinal/perirhinal cortex and spreads to the entorhinal cortex (ERC) and hippocampus, which are considered the Braak I and II stage regions. With current PET imaging resolution, it is difficult to detect tau deposition in these Braak I/II regions because signal could be present in these small regions but be blurred by signal from adjacent structures, like the meningeal dura or the skull. Therefore, in order to detect the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s pathology, we need high resolution PET to be able to separate tau deposition in these Braak I/II regions from off-target binding in adjacent structures.

| Braak Stage | Location in the Brain |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Transentorhinal cortex |

| Stage II | Entorhinal cortex and hippocampus |

| Stage III | Medial temporal lobe regions, including the amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, and fusiform gyrus |

| Stage IV | Association cortices, particularly parietal and temporal lobe regions |

| Stage V | Neocortical regions, including frontal and occipital lobe regions |

| Stage VI | Primary motor and sensory cortex |

Current PET imaging is limited in detecting tau NFTs in Braak stages I/II regions. The newer high-resolution technology would enable doctors to detect them at these early stages as well.

Dr. Chiang: Outside of imaging quality, another issue is access. Not everyone is able to access PET scanning as they are typically located in large academic centers, and people may be reluctant to travel for it — meaning thousands may be missing out on an accurate diagnosis and potentially effective treatments.

A Journey to Improve Quality and Accessibility

Dr. Goldan: I first began working on developing the technology for this new PET scanner in 2018 to solve for the challenge of obtaining ultra high-resolution imaging in these very small regions in the brain. My team developed a new depth-encoding detector, called PRISM-PET, to allow for precise 3D localization of detected radiation. This technology can detect areas of increased concentrations of [18F]MK6240, which is a radioactive tracer that binds to tau, even in structures less than 1 millimeter in diameter. We collaborated with an industrial partner to make a prototype brain scanner that was finished in 2021, and we immediately began validating the scanner. Through that process, we published the highest resolution images of phantom brain reference models for a brain PET scanner.

Achieving substantial improvements in spatial resolution in brain PET scanners means that now patient’s head movement will be the main source of image blur. Therefore, we also developed a new high-resolution electromagnetic motion tracking (EMMT) device for precise real-time estimation of both head position and orientation to achieve accurate head motion compensation.

The successful development of both PRISM -PET and EMMT technologies led us to receiving this U01 grant from the NIH. Through this grant, we seek to prove the effectiveness and reliability of the PRISM-PET/EMMT scanner to image Braak stage I/II regions of the brain both in the supine and upright position and to detect tau accumulation, even in asymptomatic individuals, serving as an early imaging biomarker of underlying pathology.

Dr. Chiang: When Dr. Goldan came to Weill Cornell Medicine in 2023 from Stony Brook Medicine, I was eager to meet with him to learn about his work. The Brain Health Imaging Institute already had several ongoing NIH-funded studies, including longitudinal imaging studies to detect early changes in the brain that could lead to Alzheimer's. I was discussing our struggles with current PET scanning resolution, and Dr. Goldan brought up the PRISM-PET/EMMT prototype and its potential to detect PET signal at 1 millimeter resolution, which could significantly aid our ability to detect pathology in the smallest regions of the brain, like the transentorhinal cortex.

Recognizing the synergies between our work, we began collaborating on how we could take his prototype and test it in Alzheimer’s. Along the way, we also began discussing the need to make this imaging modality more accessible.

Dr. Goldan: To address accessibility, we wanted to achieve two goals: make it upright and make it portable. Having the machine be upright versus supine would open a new door to studying the brain. Many studies indicate that when you're lying down, some neural networks might not respond to tasks in the same way as when you are upright. We interact with our environment in an upright orientation, so if we want to study the brain, the best position would be in the upright orientation.

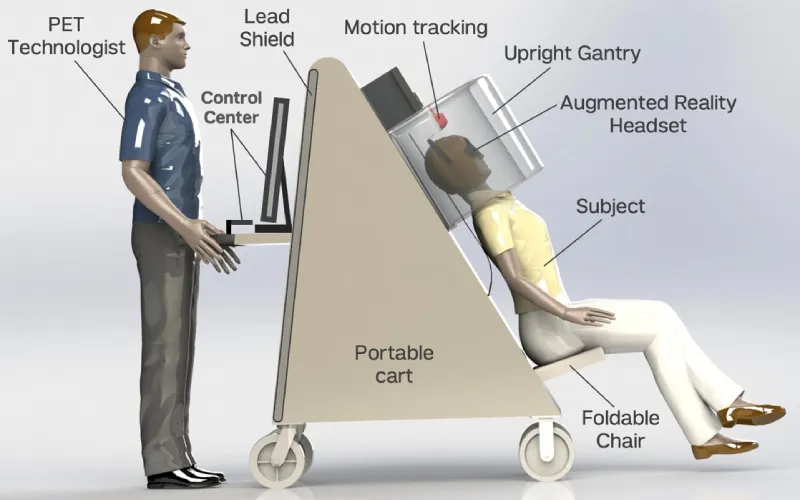

The PRISM-PET/EMMT prototype features a chair attached to the scanner, allowing for portability and use of existing imaging infrastructure to operate the machine.

Additionally, if we made the scanner upright, we could have a chair attached to the scanner, and use existing imaging infrastructure to operate the machine. This would allow us to move the machine to where the patients are. This also means you don’t need a new technician, and you don’t need a new dedicated room that is shielded. Making it portable means we can move the PET scanner to medical centers that might not have advanced brain PET imaging, enabling us to provide this highest level of care to more locations and more diverse populations.

Dr. Chiang: The upright position also solves a comfort issue. With other imaging technologies, you have to lie flat for a long time in a narrow tube, which can be very uncomfortable for our older patients who have back pain and be disorienting for our cognitively impaired patients. Also a lot of people have claustrophobia, so we hope this upright scanner may help people feel less afraid of getting imaged.

Delineating better contours of a lesion and detecting even very small brain lesions could help clinicians provide more effective therapies. We see this as having broad implications for neurology.

— Dr. Amir Goldan

Next Steps and Broader Applications

Dr. Goldan: We are currently doing two things in parallel to further develop application of this technology: We are finalizing the design of the upright scanner, which is our ultimate goal for this grant. But we are also converting one of the high-resolution PRISM-PET/EMMT prototypes into a clinical scanner that was previously tested using phantom brains and will be used to image human subjects in the supine position. We anticipate that the supine scanner will be evaluated in a clinical trial in late 2025, and the upright scanner will be ready for clinical trials in late 2026.

With this new technology, we aim to achieve early detection of tau pathology in people in small regions of the brain, even before cognitive symptoms. But high-resolution PET may also improve the imaging of conditions such as primary and recurrent brain tumors, brain metastases, seizures, and traumatic brain injuries. Delineating better contours of a lesion and detecting even very small brain lesions could help clinicians provide more effective therapies. We see this as having broad implications for neurology.

Dr. Chiang: Anything that requires brain PET imaging could benefit from this high-resolution scanner, and the increased accessibility would be ideal for patients in community-based practices.

At NewYork-Presbyterian, our radiologists have strong collaborations with physicists and engineers, designing advanced imaging tools and multimodal imaging techniques, and the neurologists, neurosurgeons, and other physicians on the frontlines, taking care of these patients. This new scanner will expand the depth and breadth of what we can offer to our patients in the hopes of improving early detection and optimizing management to delay or even prevent the development of Alzheimer’s dementia.