Danielle Brandman, MD, MAS, FAASLD

Approximately 37% of adults in the U.S., and as many as 70% of people with type 2 diabetes, have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). For Danielle Brandman, MD, MAS, FAASLD, a hepatologist and medical director of the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at NewYork-Presbyterian/

One way to do this is through screenings by primary care providers. “We see a ton of fatty liver disease in hepatology practices, but we recognize that we’re truly seeing the tip of the iceberg,” says Dr. Brandman. “The vast majority of patients with fatty liver live outside of GI and liver practices in primary care.”

Stratifying NAFLD Risk in Primary Care Patients with Diabetes

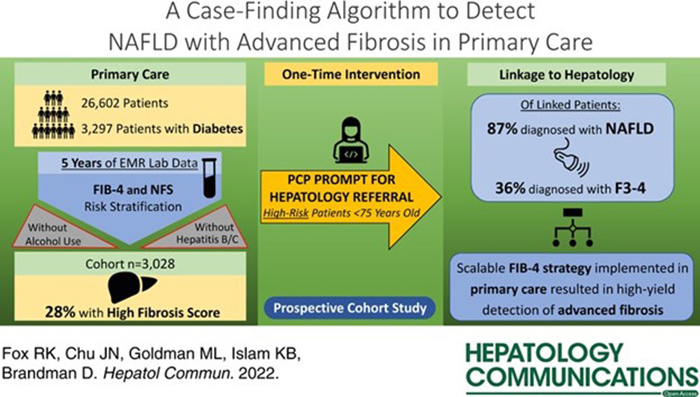

Dr. Brandman conducted a study while at the University of California, San Francisco, looking at implementing algorithms to detect NAFLD with advanced fibrosis in primary care patients with diabetes. The results of this study were recently published in Hepatology Communications.

Characteristics of NAFLD primary care cohort

Among individuals with diabetes, there is an increased risk of developing non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a more aggressive form of NAFLD. “There’s some data that suggests that [liver] fibrosis progresses more rapidly in patients with diabetes,” says Dr. Brandman. “These are really the highest risk patients for developing advanced fibrosis and subsequently liver-related morbidity and mortality.”

We see a ton of fatty liver disease in hepatology practices, but we recognize that we’re truly seeing the tip of the iceberg.

— Dr. Danielle Brandman

To reach the most at-risk patients, Dr. Brandman worked with a primary care practice with a large registry of patients with diabetes. “I partnered with a primary care provider who has a special interest in liver disease. We were both very interested in how we can identify the patients that we know are living in primary care and are high risk,” she says. “What our worry is in hepatology as well as in primary care is that the patients who have fatty liver largely have no symptoms. We know that fibrosis stage is the most important predictor of outcomes. What we really want to do is identify these high-risk patients before they become symptomatic and before they show signs of liver failure.”

Use of Non-Invasive Tests for Stratification

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology both published practice guidelines within the past year for diagnosing NAFLD in primary care. “[The guidelines say that] we should be using noninvasive scores, like the Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4), to risk stratify patients in terms of who needs to see hepatology and who can remain in primary care,” says Dr. Brandman. “These guidelines were largely based on data that came from very specialized cohorts, basically patients who had already made their way to a hepatology clinic and had a liver biopsy. Our questions were, is this applicable to the real world in undifferentiated patient? How scalable are these care pathways that have been proposed in the guidelines?”

With those guidelines in mind, Dr. Brandman and her colleagues implemented an algorithm that looked at annual FIB-4 Index and NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS). The FIB-4 and NFS both estimate the amount of scarring present in the liver based on laboratory results available in electronic medical records (EMR). The FIB-4 and NFS both estimate the amount of scarring present in the liver based on aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), platelet, and age; the NFS also includes albumin, body mass index, and presence of diabetes.

Dr. Brandman refers to the study’s algorithm as a FIB-4 first approach. “This is not completely in line with the care pathways that have been proposed, because the care pathways require that you do some sort of assessment to identify fatty liver as being present before applying FIB-4,” she says.

The researchers used existing lab data to calculate 1 FIB-4 and 1 NFS score per patient per calendar year during the study period (2015-2020). Using the highest FIB-4 and NFS scores, Dr. Brandman and the other researchers categorized patients into three groups – low-risk, indeterminate-risk, or high-risk for advanced fibrosis. Of 3,028 patients included in the study, 1,018 were low risk, 577 were indeterminate risk, and 611 were high risk.

Linkage to Specialty Care

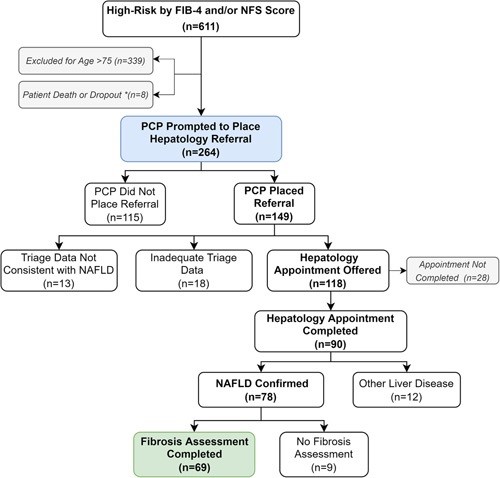

Once risk levels were stratified, the EMR of a representative sample of 10% of the high-risk group was manually evaluated to ensure that the high-risk FIB-4/NFS scores were clinically compatible with NAFLD. After excluding those ≥ 75, there were 264 individuals targeted for linkage to specialty care, with their primary care providers prompted via EMR to place a hepatology referral.

“We had a study coordinator who pended a referral to hepatology and sent a message to the doctor saying, ‘we have identified your patient as being at high risk for advanced fibrosis due to fatty liver disease. If you agree, please sign this order,’” says Dr. Brandman. “What we saw was that a little bit more than half of the primary care providers placed the referral.”

In the end, the study had:

- 149 referrals placed

- 118 hepatology appointments offered

- 90 completed hepatology appointments

- 78 individuals confirmed with NAFLD

- 69 fibrosis assessments completed

Hepatology referral pathway

“I think really shows that this FIB-4 first approach can work in this patient population,” says Dr. Brandman. “I view this study as the real world clinical translational study bringing the evidence and guidelines to the bedside.”

I view this study as the real world clinical translational study bringing the evidence and guidelines to the bedside.

— Dr. Danielle Brandman

Bringing a FIB-4 Approach to NewYork-Presbyterian

Dr. Brandman has been working to implement similar algorithms to risk stratify NAFLD patients at NewYork-Presbyterian. She notes that Ilan Weisberg, MD, division chief of gastroenterology at NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist has developed a tool like the one Dr. Brandman created at UCSF to identify patients at-risk for NAFLD.

“We’re working with NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist as well as NewYork-Presbyterian Queens to use similar tools to help primary care providers and to automate the process of identifying these patients,” she says. “I think what we really need is true automation. [It’s important that we] launch the EMR tools to reach our non-Manhattan sites and speak with the primary care providers [in Manhattan] as well.”

The importance of having a primary care champion at NewYork-Presbyterian is paramount. “What my project taught me is that you need a primary care champion to drive this forward,” says Dr. Brandman. “That’s something I really want to work on in terms of relationship building and communication. If you look at all the care models for fatty liver disease, there is overlap. It’s not like hepatology owns them or primary care owns them. It really has to be a shared model, and I very much want to be a part of that.”

Dr. Brandman notes that this collaboration will be particularly important in the coming months. “There are two drugs that are in phase 3 trials now for treatment of fatty liver disease,” she says. “I think once we have these approved drugs, it’s going to make processes like this and identifying at-risk patients much more important.”