The inner ear is a well-protected and difficult-to-access part of the body, making it a challenge to administer therapy or perform diagnostics. Recognizing the need to safely access the inner ear to diagnose and treat a variety of conditions, Anil K. Lalwani, M.D., a otologist and neurotologist at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia, and Jeffrey W. Kysar, Ph.D., a mechanical engineer at Columbia, teamed up to develop microneedle technology with the promise of direct access to the inner ear without causing damage.

This surgical advancement has implications for precision medicine in otology, including better diagnosis of sudden hearing loss and an improved understanding of inner ear conditions, like Meniere’s disease, through direct fluid sampling from the inner ear. The microneedle may also be able to deliver novel treatments like gene therapy through direct injection into the cochlea.

“Right now, we can get an MRI scan just to make sure there’s no tumor but otherwise, there is no additional diagnostic test or tissue biopsy that we can do safely for the inner ear,” says Dr. Lalwani. “It is one of the hardest bones in the body, so hard that it’s been known to deflect bullets. It only has one membranous portal through which you can access it, the round window membrane, which is just a little bit bigger than Lincoln’s ear on a penny. Normally any kind of access would cause hearing loss or vertigo. Our current surgical tools are so large that anything going in the round window membrane of the inner ear would cause damage.”

Dr. Lalwani and Dr. Kysar have been working on this medical and engineering dilemma for more than a dozen years, evolving their design as the technology and materials improved. After years of successful testing in preclinical models with guinea pigs and mice, they are now poised to launch a clinical trial in humans that uses the novel microneedle to aspirate fluid in the inner ear at the time of a cochlear implant. They plan to enroll 100 patients and expect to answer the essential questions of safety and feasibility within 18 months.

We knew that if we could just make tools sufficiently small below this critical size, then we would be able to perforate the round window membrane safely. We did not know what that critical size was, but we knew that it existed based on the math.

— Dr. Jeffrey Kysar

Engineering the Microneedle

Understanding how the microneedle should be designed began with Dr. Kysar listening to Dr. Lalwani and other surgeons describe their experiences working with the round window membrane during surgery. “They all said that even if they use the smallest surgical tool they have to try to penetrate the round window membrane, it will invariably rip across its entire length,” he says. “As an engineer, I recognized the membrane is in residual tension.”

With residual tension, a small perforation is stable, but a larger one will create a rip. “We knew that if we could just make tools sufficiently small below this critical size, then we would be able to perforate the round window membrane safely,” says Dr. Kysar. “We did not know what that critical size was, but we knew that it existed based on the math.”

That began a search for ways to produce microneedles that would be small enough for safe access. The standard method at the time relied on the same technology used to make computer chips and produces the needles from silicon. Unfortunately, that technology made the needle “as brittle as window glass,” Dr. Kysar says, creating a risk that it could break off in the ear.

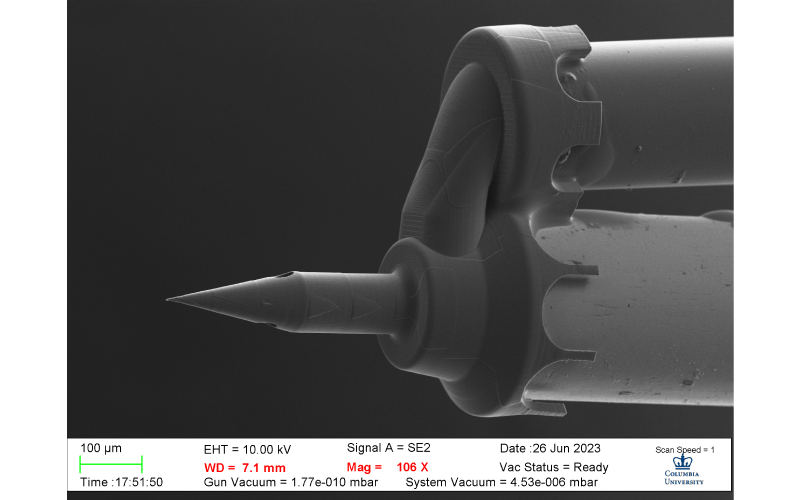

Eventually they learned of new commercialized technology that uses a 3D printing method called two-photon photolithography, which allows the creation of devices with voxel (the 3D version of a pixel) resolution as precise as 200 nanometers. To safely perforate the round window membrane, Dr. Kysar and Lalwani created a microneedle measuring approximately 100 micrometers in diameter — or just larger than the diameter of a strand of hair — with an ultra-sharp tip measuring about one half of 1% of the diameter of a hair.

Dual-lumen microneedle that injects through one lumen and aspirates simultaneously through the other lumen to maintain constant pressure with cochlea. Published with permission of Dr. Anil Lalwani and Dr. Jeffrey Kysar.

As the microneedle perforates the membrane, it pushes through the membrane’s connective fibers, causing a small amount of damage — but no tearing — that heals within 48 to 72 hours. The microneedle is not solid but is designed with two lumens, allowing the device to insert and remove fluid simultaneously. This helps to maintain a constant volume of liquid inside the inner ear so that the pressure does not change, which could lead to hearing loss or vertigo, Dr. Kysar says.

Preclinical Studies Paved the Way

Over the last several years, Dr. Lalwani, Dr. Kysar, Columbia biomedical engineer Elizabeth S. Olson, Ph.D., and other colleagues have conducted a series of animal studies to demonstrate that the microneedle can be used safely without causing hearing loss; that even multiple injections across the round window membrane are safe; and that the microneedle can both remove and inject fluid in the inner ear, enabling fluid sampling for diagnosis and the delivery of therapeutics.

We believe this is going to open up the whole field of precision inner ear medicine, both diagnostically and therapeutically.

— Dr. Anil Lalwani

Most recently, they showed how the microneedle could be used to deliver novel gene therapies in guinea pigs. In a study published in Otology & Neurotology, they tested the feasibility of microneedle injection of small interfering RNA (siRNA) and lipofectamine through the round window membrane for cochlear transfection. Fluorescence confirmed successful transfection within the cochlea at 24 and 48 hours, with no signs of cochlear toxicity at five days.

Dr. Lalwani and Dr. Kysar credit their ability to develop the microneedle to their multidisciplinary collaboration. The pair met after being introduced by their postdoctoral fellows and immediately shared a curiosity about how to solve the problem of accessing the inner ear. NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia’s programs devoted to technology acceleration also gave them access to critical funding opportunities and educated them on how to translate science discoveries into medical technology through understanding of the commercial market and the device approval process.

After more than a decade of research and development, Dr. Lalwani is hopeful the soon-to-be-launched human trial will reflect the results of the preclinical work. “As our work has evolved, the field appears ready for this technology and this implementation,” says Dr. Lalwani. “We believe this is going to open up the whole field of precision inner ear medicine, both diagnostically and therapeutically.”

Anil K. Lalwani and Jeffrey W. Kysar are two of the co-founders of and have equity in Haystack Medical, Inc., that will commercialize microneedle and associated technology to facilitate medical access to the middle and inner ear.